.webp)

.webp)

The information below is the Valencian version of the wall panels, machine invention plinths, and timelines which are displayed throughout this exhibition. The information is ordered to accompany you on your journey through the museum.

Navigation:

Navigate to any section by using the menu below, or by simply scrolling up or down on your mobile device.

The up-arrow at the end of each section will take you back to the top menu.

Grande Experience: Creator & Producer of Leonardo da Vinci – 500 Years of Genius

Grande Experiences is a global leader in the ideation, development, production, licensing, and installation of expansive exhibitions and immersive cultural experiences. Renowned for blending entertainment and education seamlessly, our distinguished portfolio includes the internationally acclaimed Van Gogh Alive, Monet & Friends Alive, Dalí Alive, Leonardo da Vinci – 500 Years of Genius, Connection, and Street Art Alive, all of which have garnered recognition for their captivating narrative and innovative presentation.

Grande Experiences has an unsurpassed track record of displaying our exhibitions and experiences more than 275 times across 200+ cities, transcending linguistic and geographic boundaries in 33 languages, spanning 6 continents to an audience of more than 25 million.

Headquartered in Melbourne, Australia, Grande Experiences boasts a global presence with satellite offices strategically positioned in the UK and Italy. Beyond our touring experience division, we proudly own and operate THE LUME Melbourne, the world’s largest digital immersive art gallery, and Museo Leonardo da Vinci, located in the prestigious Piazza del Popolo in central Rome. Furthermore, Grande partners with The Indianapolis Museum of Art, Newfields for THE LUME Indianapolis.

Leonardo da Vinci – 500 Years of Genius: The Experience

Embark on a journey into the extraordinary mind of Leonardo da Vinci, and be inspired by his unwavering commitment to learning all there is to learn.

With nature as his muse, Leonardo’s notebooks brim with acute observations, anatomical studies and detailed sketches. From how light bounces, to how a shadow falls and how perspective shapes reality. His artistic techniques to capture the natural world were groundbreaking.

This level of detail and understanding brought life to his masterpieces, as seen in the iconic The Last Supper and Mona Lisa. His belief in the connection between art and science marked a transformative moment in portraiture and beyond.

Artist to innovator, Leonardo’s inquisitive mind ventured beyond his art. Meticulous dissections of the human body provide unprecedented insights into anatomy. Ingenious concepts for flying machines, engineering designs and more reveal a mind that transcends beyond imagination.

Step into the Renaissance and see how Leonardo formed relationships with powerful and influential patrons including the Medici family and Ludovico Sforza of Milan. Get a glimpse into the dance between creative freedom and the demands of benefactors to understand the challenges faced by a visionary during this extraordinary and revolutionary time.

Leonardo da Vinci – 500 Years of Genius is a homage to the insatiable curiosity of Leonardo da Vinci. From nature to art, innovation to influence and the unparalleled contributions that continue to captivate audiences.

Leonardo da Vinci

1452-1519

Born in Anchiano, near the Tuscan town of Vinci on 15 April 1452, Leonardo was the illegitimate son of a notary, Ser Piero and a peasant woman, Caterina, therefore he did not undertake a formal education, instead, he learned through the power of observation.

Leonardo lived with his father and stepmother until around the age of 14, until he became an apprentice to Andrea de’Cioni, known as Verrocchio and one of the most esteemed Florentine artists of the time.

In Verrocchio’s workshop, Leonardo honed his skills alongside other painters such as Perugino and Botticelli. A student of light and shadow, Leonardo created multiple light sources on faces and objects to recreate what he saw in nature.

His deep curiosity about nature found expression in every sort of artistic discipline, using scientific observations to enrich his paintings and sculptures, which showed extraordinary precision and accuracy.

When Leonardo painted The Baptism of Christ, depicting a young angel holding the robe of Jesus, Verrocchio marvelled at the depth and colour of Leonardo’s technique of oil painting. There was no denying his young protégé’s talent.

He would go on to create some of the most celebrated works of art the world has known. Mona Lisa, The Last Supper, Lady with an Ermine, Virgin of the Rocks (two versions) and controversially the most expensive art ever sold Salvator Mundi – selling at auction in 2017 for over US$450m.

Leonardo was also a military strategist and invented the forerunner to the military tank, a giant crossbow, a multi-directional gun machine, the bullet and bridges for armies and more.

He dreamed of creating the ‘ideal city’ with a healthy environment that would rid the world of the plague. And foreshadowed the invention of the automobile, improved ball bearing and gearing systems and sketched the mechanisms for a robot.

Tall and handsome, left-handed, likely to have been vegetarian, a pacifist, preferred the company of men and was not particularly religious, historic accounts of Leonardo suggest he was a very unique individual.

“Every slightest motion performed by an object in space is maintained by its impetus.”

“Why does the eye see a thing more clearly in dreams than the imagination when awake?”

“Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.”

“Nature never breaks her own laws.”

“The artist sees what others only catch a glimpse of.”

“The greatest deception men suffer is from their own opinions.”

“Knowledge of all things is possible.”

“Learning never exhausts the mind.”

.svg)

Codices

The majority of Leonardo’s handwritten notes and drawings of his observations are bound into manuscripts called codices. There are about 7,200 pages that have survived until today, out of approximately 25,000 pages.

Leonardo rarely put dates on his pages and much of the order has been lost. After Leonardo’s death, his notebooks were bequeathed to his favourite apprentice, Francesco Melzi who held onto most of them and kept them safe until he died in 1579.

By the late 16th century many of the remaining notebooks came into the possession of Pompeo Leoni, a sculptor in the Court of the King of Spain. They were disassembled and the more interesting pages were sold or reorganised. Pompeo Leoni tried to organise them by subject – an admirable endeavour, but one that ultimately only resulted in disturbing the original order of the pages, which may have been key to our understanding of Leonardo’s thought processes.

Each of the new books created by this process is now known as a codex. Over time, most of Leonardo’s ten known codices have found their way into various museums, archives or libraries around the world, with only one remaining in private hands. Two of the codices were unknown until 1966 when they were found by chance in the National Library of Madrid.

Each of the new books created by this process is now known as a codex. Over time, most of Leonardo’s ten known codices have found their way into various museums, archives or libraries around the world, with only one remaining in private hands. Two of the codices were unknown until 1966 when they were found by chance in the National Library of Madrid.

Codex Arundel

This collection, comprising a paper manuscript bound in Moroccan leather, is housed in the British Library in London. It contains 238 pages of varying sizes that have been cut and removed from other manuscripts. Most of the pages can be dated to between 1480 and 1518. The notes deal with a variety of subjects, including geometry, weights and architecture. Among the pages are notes concerning the royal residence of François I at Romorantin, France.

Codex Ashburnham

These two cardboard-bound manuscripts, held in the Institut de France, Paris, consist of pages stolen from codices A and B in the nineteenth century and eventually sold to Lord Ashburnham. The collections mainly contain pictorial studies and assorted drawings which Leonardo is believed to have drawn between 1489 and 1492. Part II relates solely to painting.

Codex Atlanticus

This Codex kept in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, encompasses Leonardo’s entire career, from 1478 to 1519. Today it consists of twelve leather-bound volumes, comprising 1,119 pages of different sizes. Various themes are touched on, including mathematics, geometry, astronomy, botany, zoology and the military arts. The name “Codex Atlanticus” derives from the original arrangement of all the sheets in a single large-sized volume, akin to an atlas. Codex Atlanticus was created around the end of the sixteenth century when sculptor Pompeo Leoni dismembered the original Leonardo manuscripts, separating the scientific and technical drawings of Codex Atlanticus from the naturalistic and anatomical ones that are today scattered among the other codices, most notably the Royal Windsor collection.

Codex Forster

These three parchment-bound paper manuscripts are housed in London at the Victoria and Albert Museum. The manuscripts are known as Forster I (two parts, one completed from 1487–1490 and one in 1505), Forster II (1495–1497) and Forster III (1490– 1496). They include studies on geometry, weights and hydraulic machines.

Codices of the Institut de France

The codices held at the Institut de France, Paris, comprise twelve paper manuscripts labelled A to M, variably bound in parchment, leather and cardboard. They vary widely in size, from approximately A7 (10 x 7 cm, Codex M) to A4 (Codex C, 31 x 22 cm). A range of subjects are covered, including military art, optics, geometry, the flight of birds and hydraulics. The majority of the pages are thought to date from 1492 to 1516.

Codex Leicester

This leather-bound paper manuscript was purchased by Bill Gates in 1995. It comprises 64 sheets, dedicated primarily to studies in hydraulics and the movement of water but also includes studies in geology and astronomy. The manuscripts can be dated from 1504 to 1506.

Codex ‘On the Flight of Birds’

Held in the Biblioteca Reale of Turin, this collection includes 17 of the 18 original pages in which Leonardo methodically analyses the flight of birds, paying close attention to the mechanics of flight as well as air resistance, winds and currents. The pages can be dated to approximately 1505.

The Madrid Codices

These two manuscripts were discovered in the National Library of Madrid in 1966, bound in red Moroccan leather, after being hidden for years. To facilitate easy identification, they were named Madrid I and Madrid II. Madrid I consists of 192 sheets penned between 1490 and 1496, most of which focus on mechanics. Madrid II is primarily dedicated to studies in geometry and dates from 1503 to 1505.

Codex Trivulzianus

This codex, held in the Biblioteca Trivulziana at the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, contains studies in architecture and religious themes, as well as numerous pages testifying to Leonardo’s efforts to improve his literary education. Only 55 of the original 62 pages remain, mostly dating from 1487 to 1490.

Windsor Folios

Held in Windsor Castle’s Royal Collection, these folios comprise approximately 234 unbound sheets containing nearly 600 drawings of various sizes, composed between 1478 and 1518. The subjects of the drawings include anatomy, geography, cartography, horse studies and even caricatures.

.svg)

Engineering Excellence

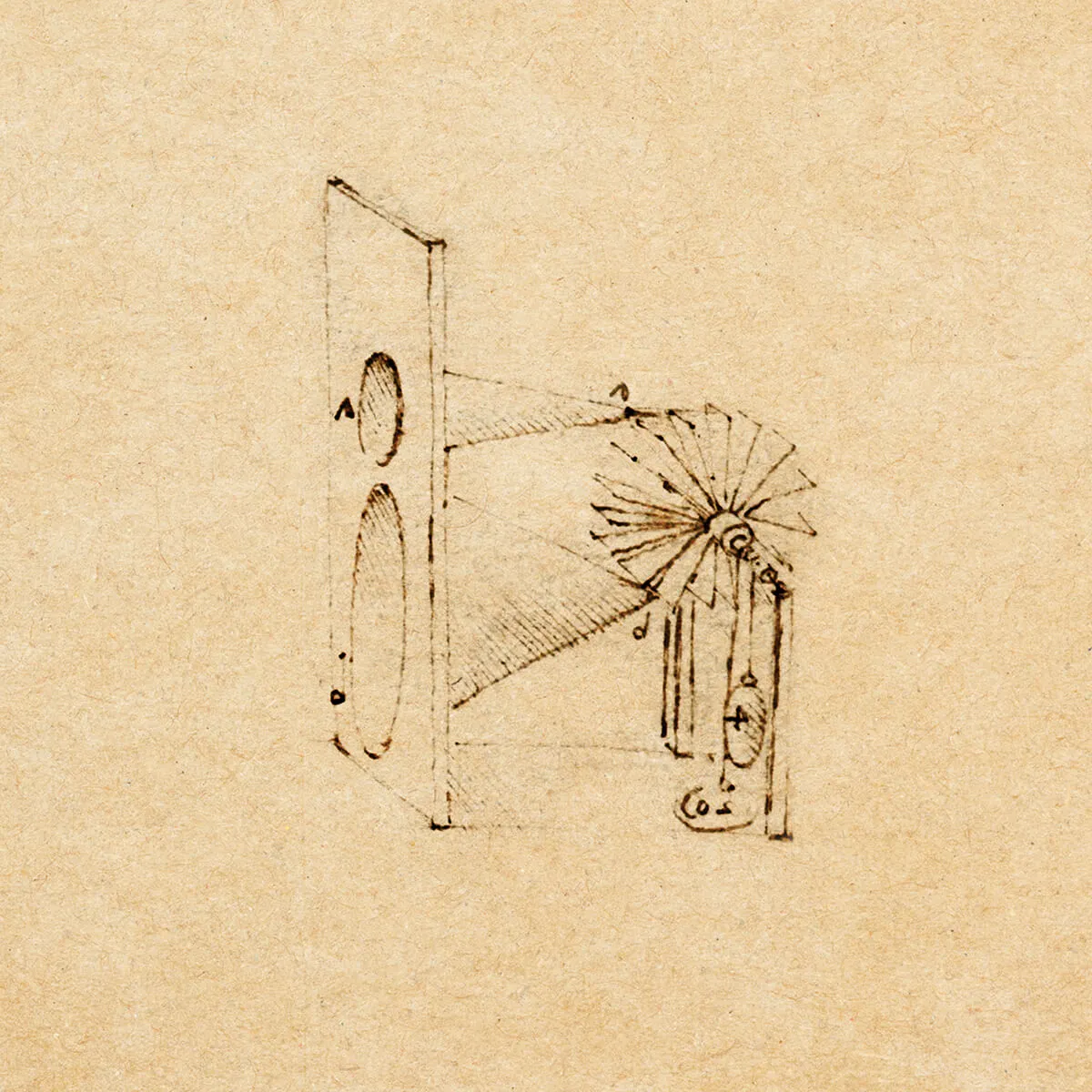

Fascinated with optics, Leonardo crafted ‘burning mirrors’ that could focus sunlight to melt metal. His observations of how light behaves were not only used in his art but also laid the foundation for future discoveries.

Extending his artistic eye to the function of everyday machines, Leonardo analysed how they worked and translated his findings into detailed mechanical drawings that are hailed as works of art. Some sketches are refined, capturing the essence of the device, while others are swift and rough, focusing on the mechanics alone. Hasty notes accompany his observations and ideas for how the machine could be further used.

An unwavering interest in mechanics and a relentless pursuit of perfection were a constant theme throughout his life.

Leonardo developed civil machines, such as hoists for lifting hefty materials, textile machines, cranes, drills, construction-site machines and excavators all with the view to transform the tedious into a streamlined operation.

“There are three classes of people: Those who see. Those who see when they are shown. Those who do not see.”

– Leonardo da Vinci

.svg)

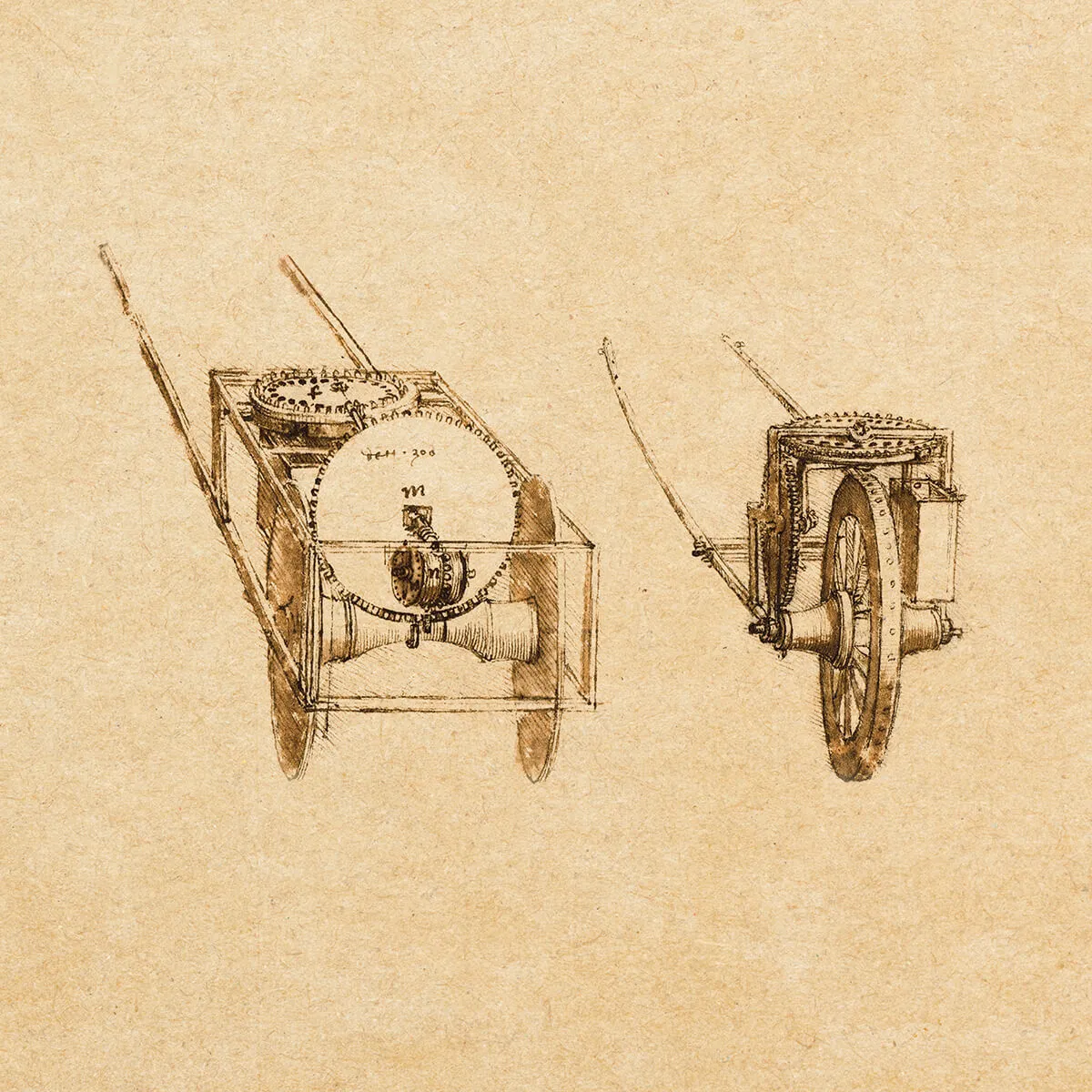

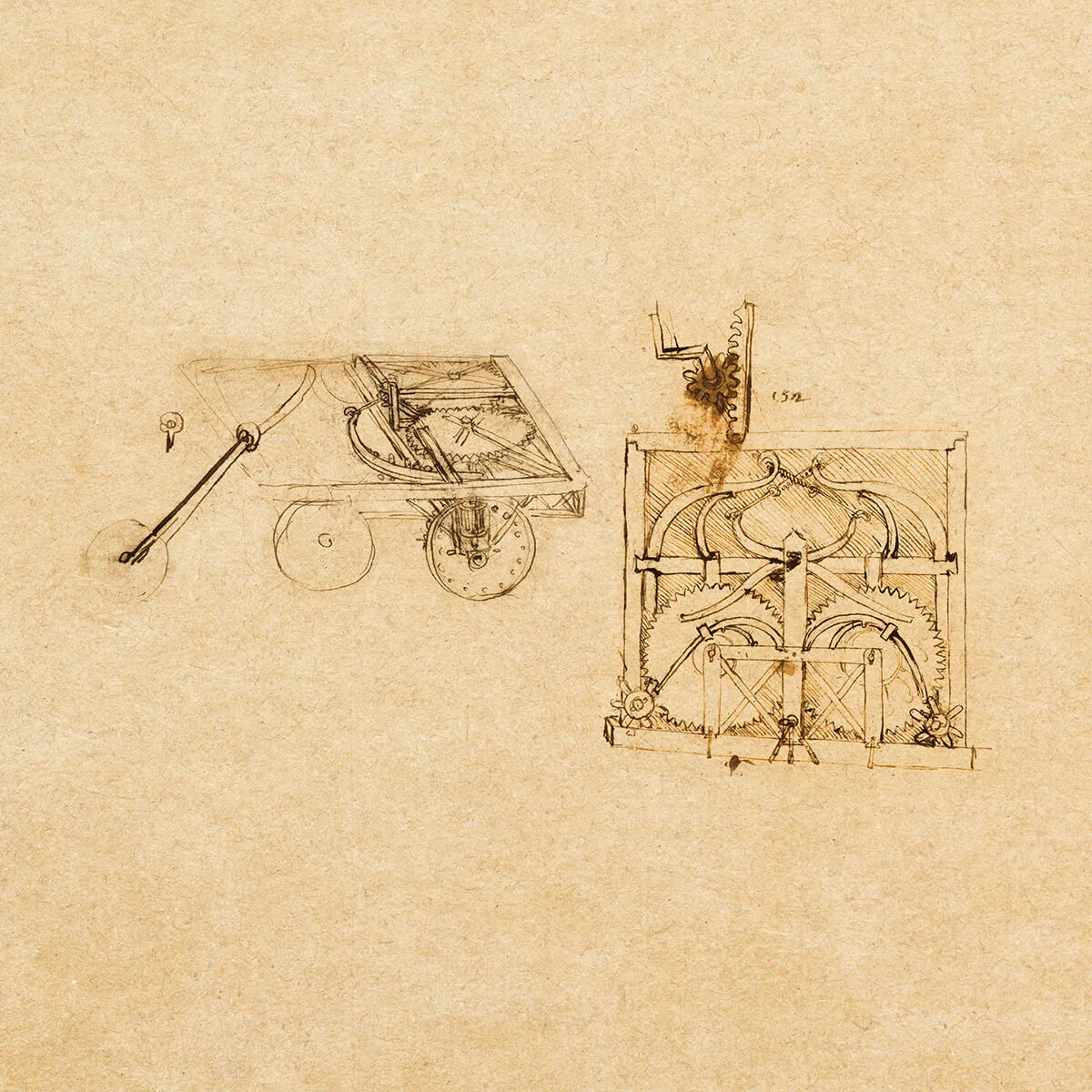

Odometer

This odometer measures distance. Leonardo’s design looks like a wheelbarrow with gears attached. Every time the cartwheel makes a complete turn, it moves a smaller vertical wheel forward by one notch.

The horizontal wheel moves one notch, dropping a pebble or wooden ball from a small hole into a box. You can figure out the distance travelled by counting how many pebbles or balls are in the box and then multiplying by the wheel’s circumference. This design is a version of a tool created by the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius.

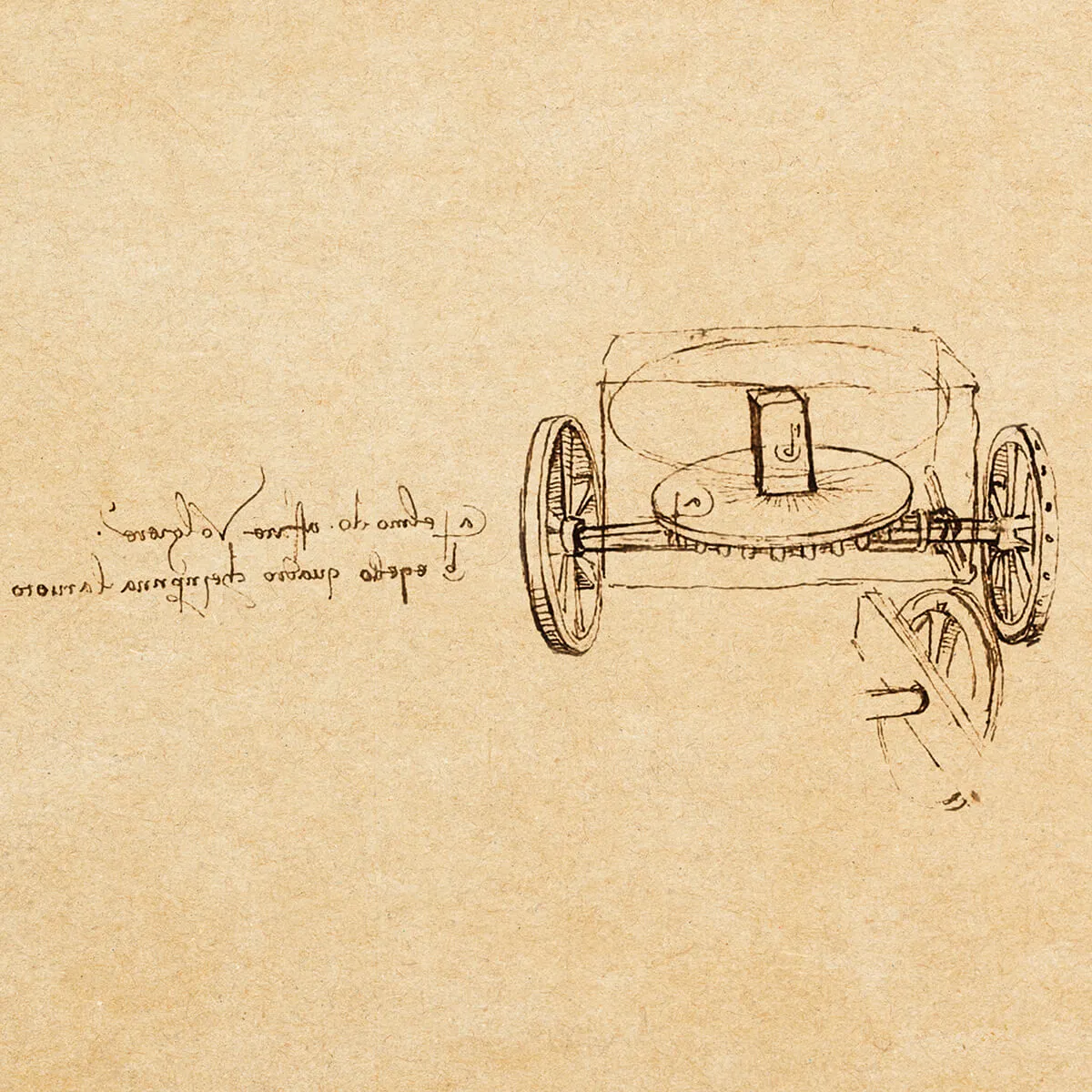

Crank-Operated Cart

This design (at the top of the folio) transmits motion to the axle of a wagon. When the crank is turned, the toothed wheel moves and engages a sprocket, which drives the axle to the wheel.

Only one wheel gets power, allowing the other wheel to turn at a different speed when the wagon makes a turn. A car differential performs the same function today.

Self-Propelled Car

Leonardo da Vinci’s self-propelled car was a groundbreaking invention and is considered one of the earliest concepts of a mechanised vehicle.

Originally designed for a theatre production in Milan, Leonardo’s cart-like vehicle design was powered by a complex system of springs, gears, and mechanisms and it could move on its own. The vehicle could move either in a straight line or along a curved path, and its rear wheels were equipped with differential gears allowing them to rotate independently.

Leonardo’s automobile concepts laid the groundwork for advancements in automotive engineering, influencing the development of modern automobiles centuries later.

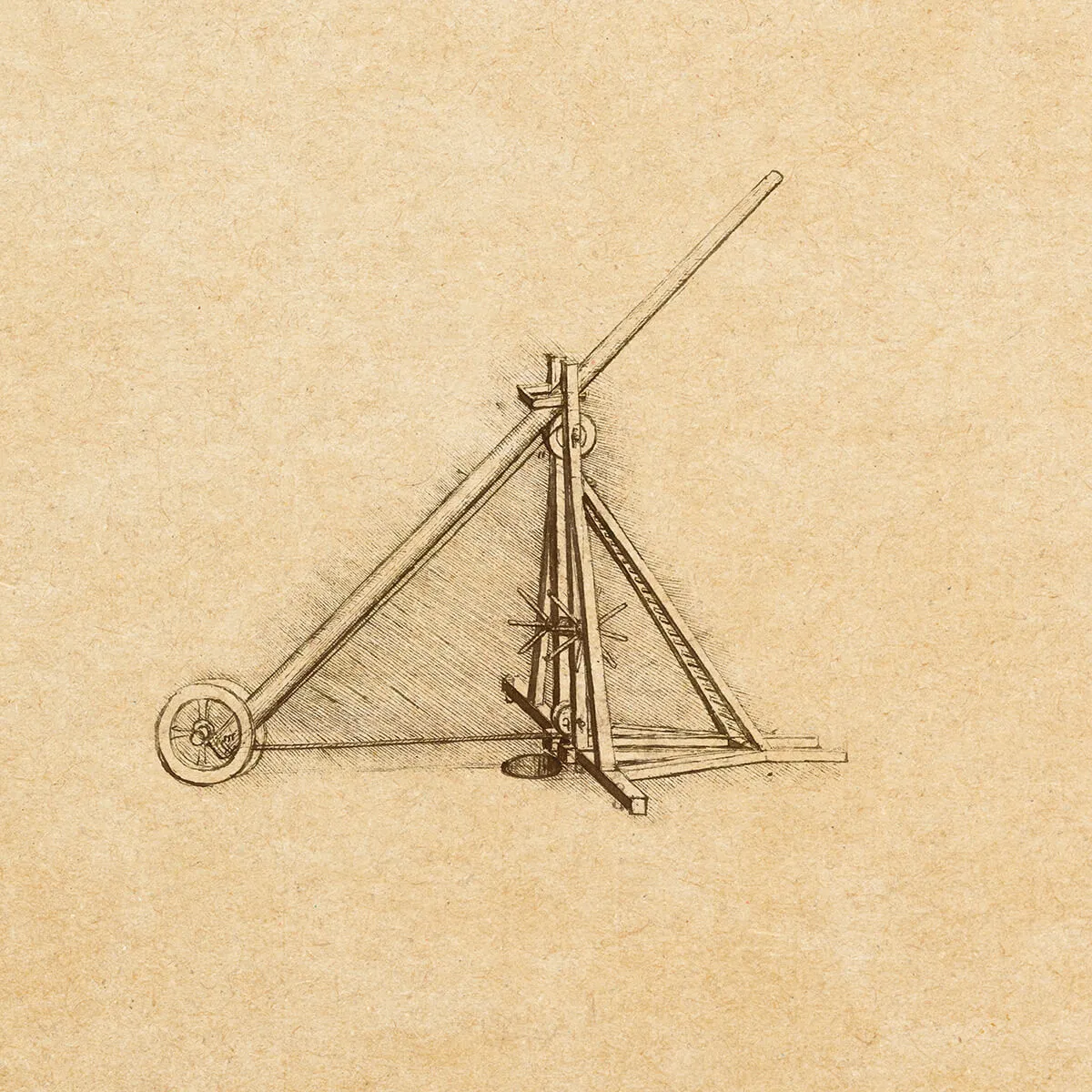

Pole-Erecting Machine

This is a simple version of a machine for erecting pillars and poles. Leonardo drew on earlier designs by the Italian engineer Francesco Martini, among others. The bottom of the pillar is on a wagon with two wheels that can be pulled forward with a rope, either straight (horizontal) or at an angle (oblique).

The horizontal rope, which winds around a pulley connected to a winch system, requires less effort because the friction stays the same as the pillar rises. But if you use an oblique rope, the force needed on the rope keeps increasing, and by the end, all the pillar’s weight is on the rope.

The Ideal City

The plague of 1484 spread quickly in the old, narrow, dark and crowded streets of many Italian towns. When it ended, many architects sought ways of improving the cities to make

them healthier and less cramped.

Leonardo conceived ideas for a multilayered city, with dwellings placed at right angles to each other on wide streets, buildings of several stories, and navigable canals to connect the city to the sea. Some, with their arched colonnades, reflect classical architecture.

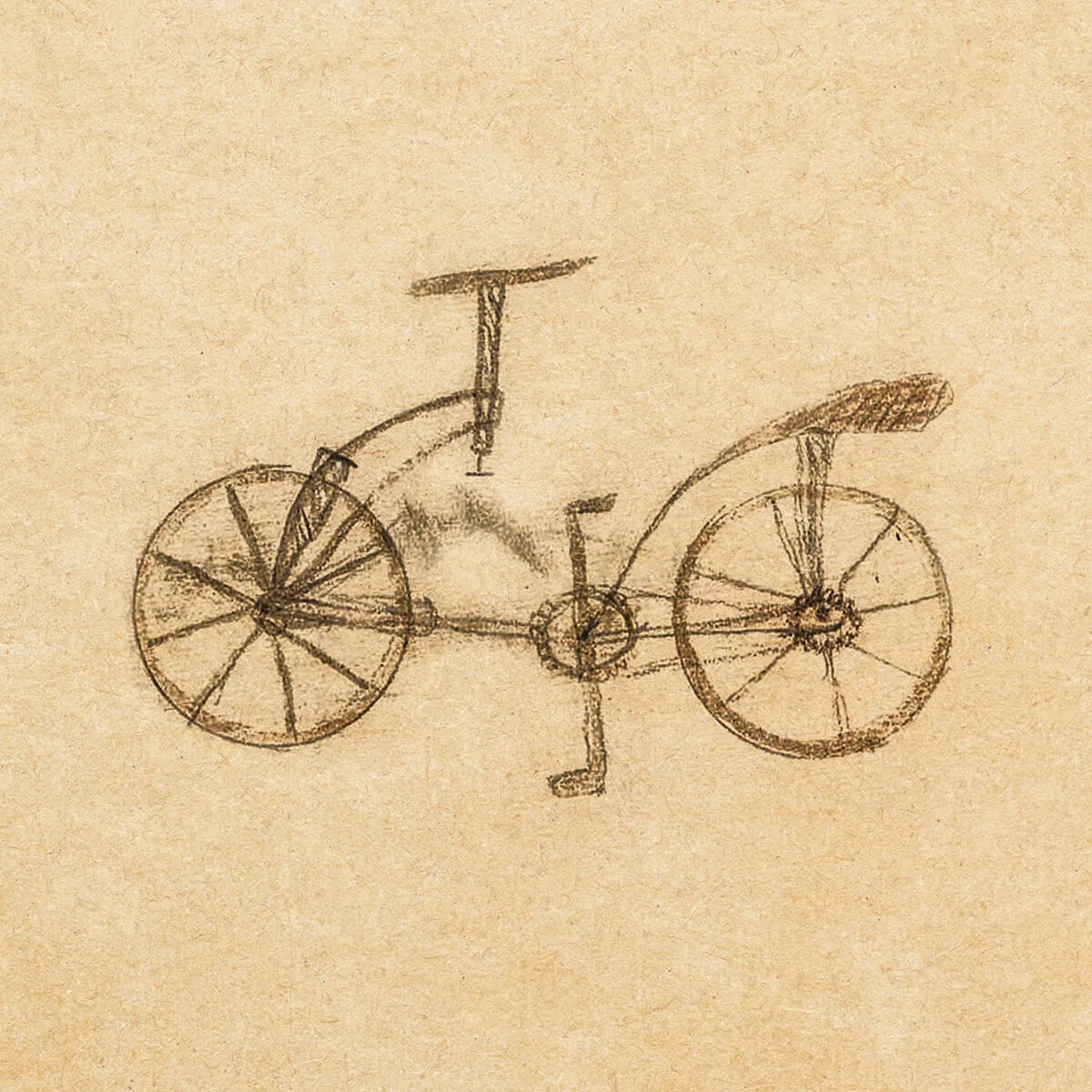

Bicycle

Although Leonardo did conceptualise and sketch human-powered machines, including designs that resemble bicycles, the discovery of this drawing among Leonardo’s papers has raised much controversy.

Restoration work on the Codex Atlanticus during the 1960s indicated that the drawing is probably a twentieth-century hoax and that Leonardo did not invent the bicycle in its complete form.

Also, Leonardo’s heavy black lines can usually be seen on the other side of a page, but sketches of the bicycle parts, in particular, can’t be seen. The sketch was completed in graphite, which was not discovered until some decades after Leonardo’s death.

.svg)

Father of Flight

With an in-depth analysis of bird and bat flight patterns coupled with a detailed study of their anatomy, Leonardo replicated the movement of these airborne creatures through machinery.

Confronted with the reality that humans, with less than a quarter of a bird’s muscle strength in the arms and chest, could not achieve flight through direct imitation, Leonardo shifted his focus to understanding the wind including velocity and how to use air currents to reach significant altitudes.

Leonardo’s visionary ideas laid the groundwork for the myriad of flying machines that define modern aeronautics, from gliders and aeroplanes to helicopters and parachutes, all of which echo in the present era of aviation.

“There shall be wings! If the accomplishment be not for me, ‘tis for some other.”

– Leonardo da Vinci

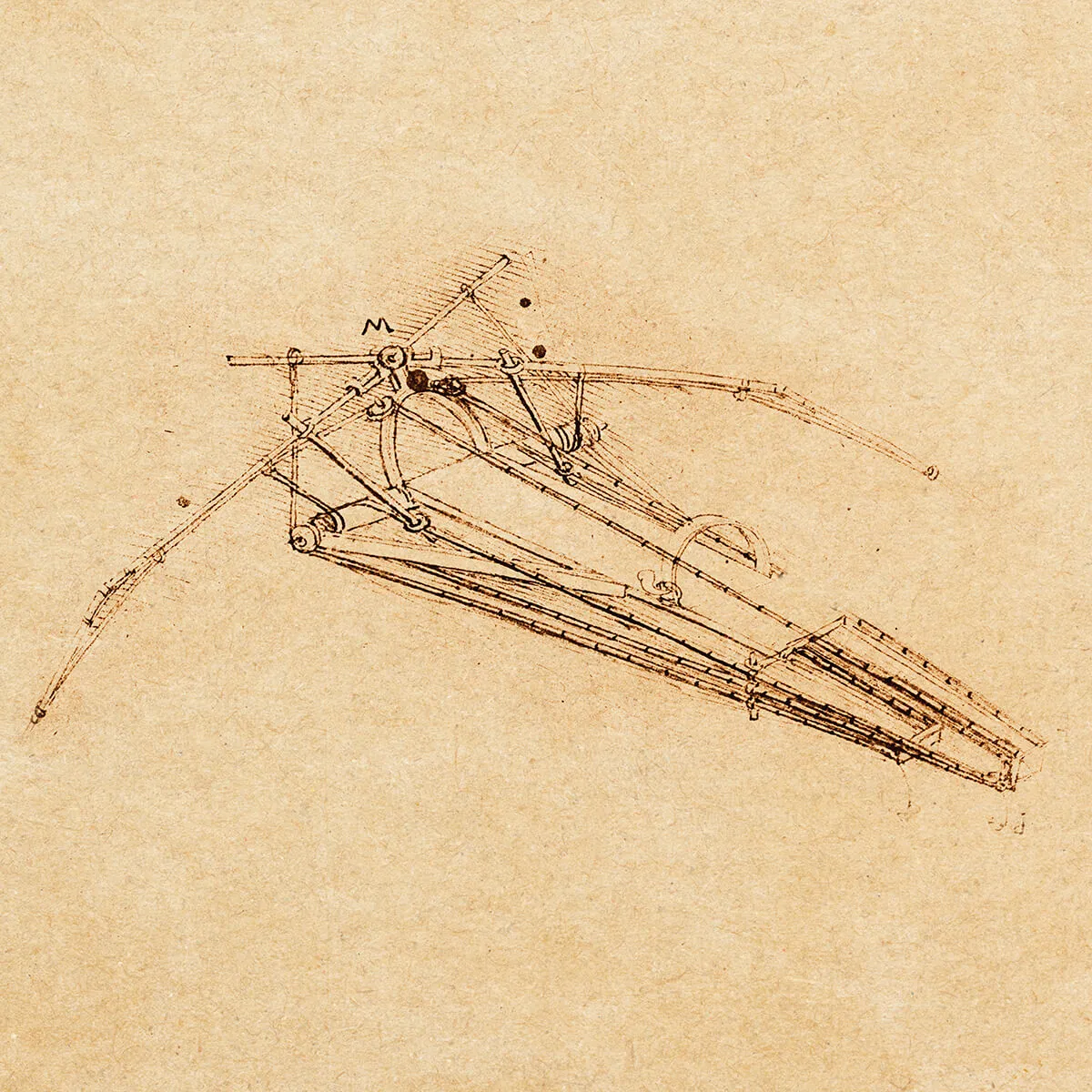

Glider

This flying design is based on how the wings of a bird move.

The pilot, held up by straps, hangs vertically at the centre of the machine and balances by moving their lower body. The inner part of each wing is fixed, while the outer part can bend. The pilot moves the wings using a system of ropes and pulleys operated by handles.

Although this machine needed a lot of human strength and couldn’t really work, it was an important step forward in the study of aerodynamics.

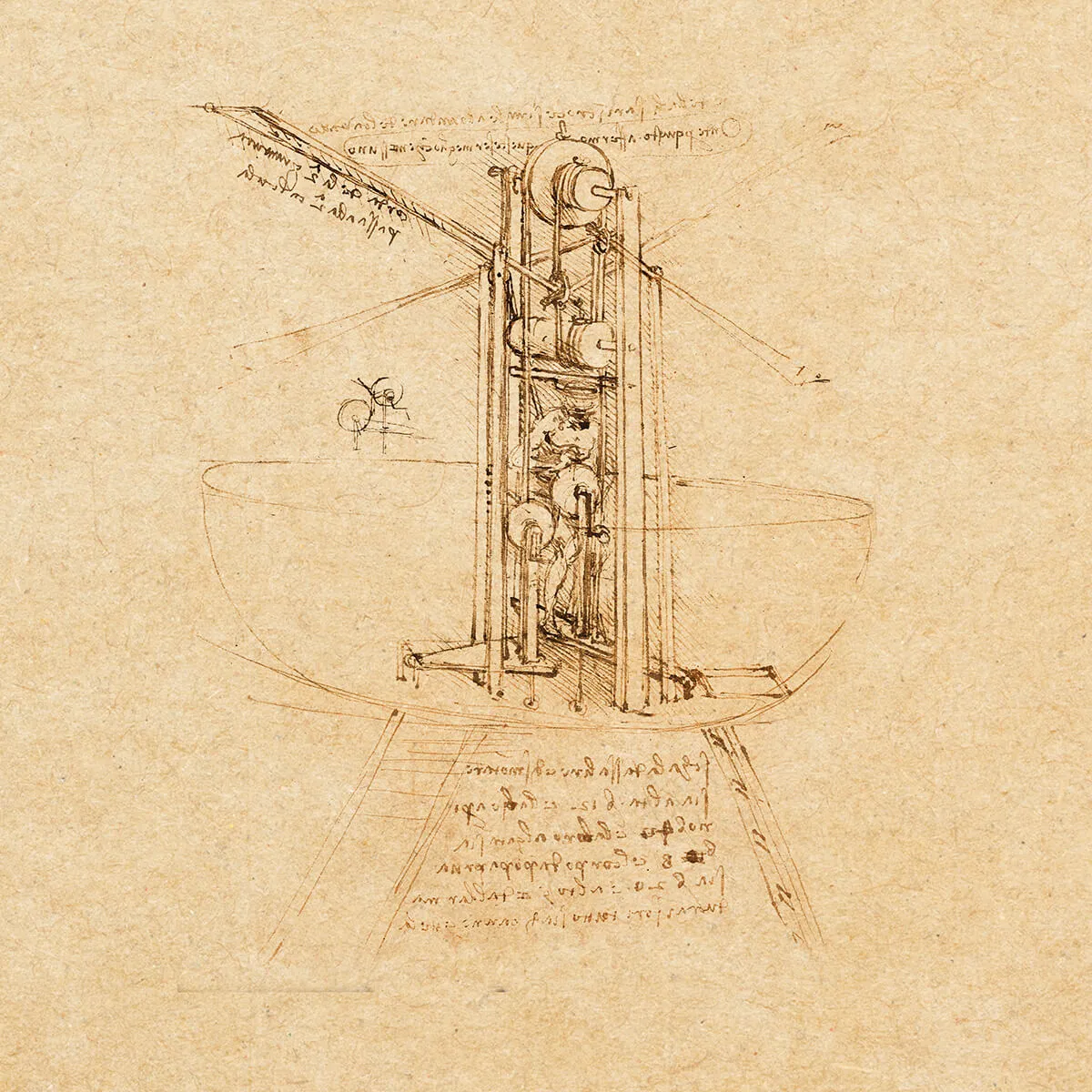

Vertical Flying Machine

In this design, the pilot stands upright in the centre of a large machine. To get it off the ground, they have to use their arms, legs, and even head to move parts of the machine up and down. Leonardo wanted to use every part of the body to maximise energy.

The machine is 12 metres (40 feet) long with a 24-metre (80‑foot) wingspan, and it has a 12-metre (40-foot) retractable ladder with shock absorbers.

Leonardo thought it was important to have two pairs of wings that beat in a ‘crisscross’ pattern, similar to how a horse moves.

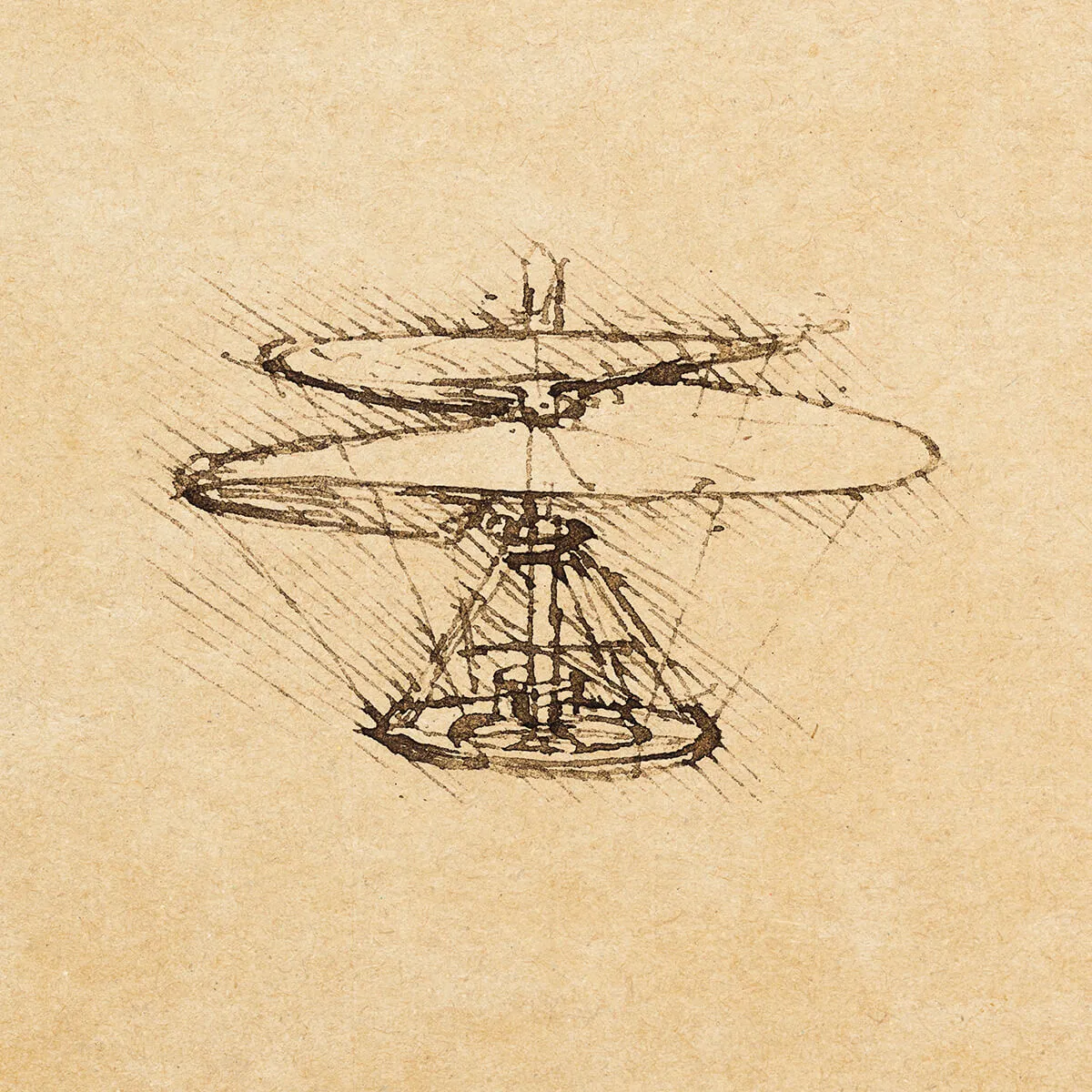

Aerial Screw

Children in mediaeval times played with toys called ‘whirligigs.’ These toys had blades on a central shaft that spun and moved upward. Leonardo likely used this idea for his design of a rising screw. Four people on a platform at the base would push bars to turn the shaft. As the linen-covered blades spun, they would create an upward force.

Though this machine probably couldn’t fly, it’s seen as the early inspiration for today’s helicopters.

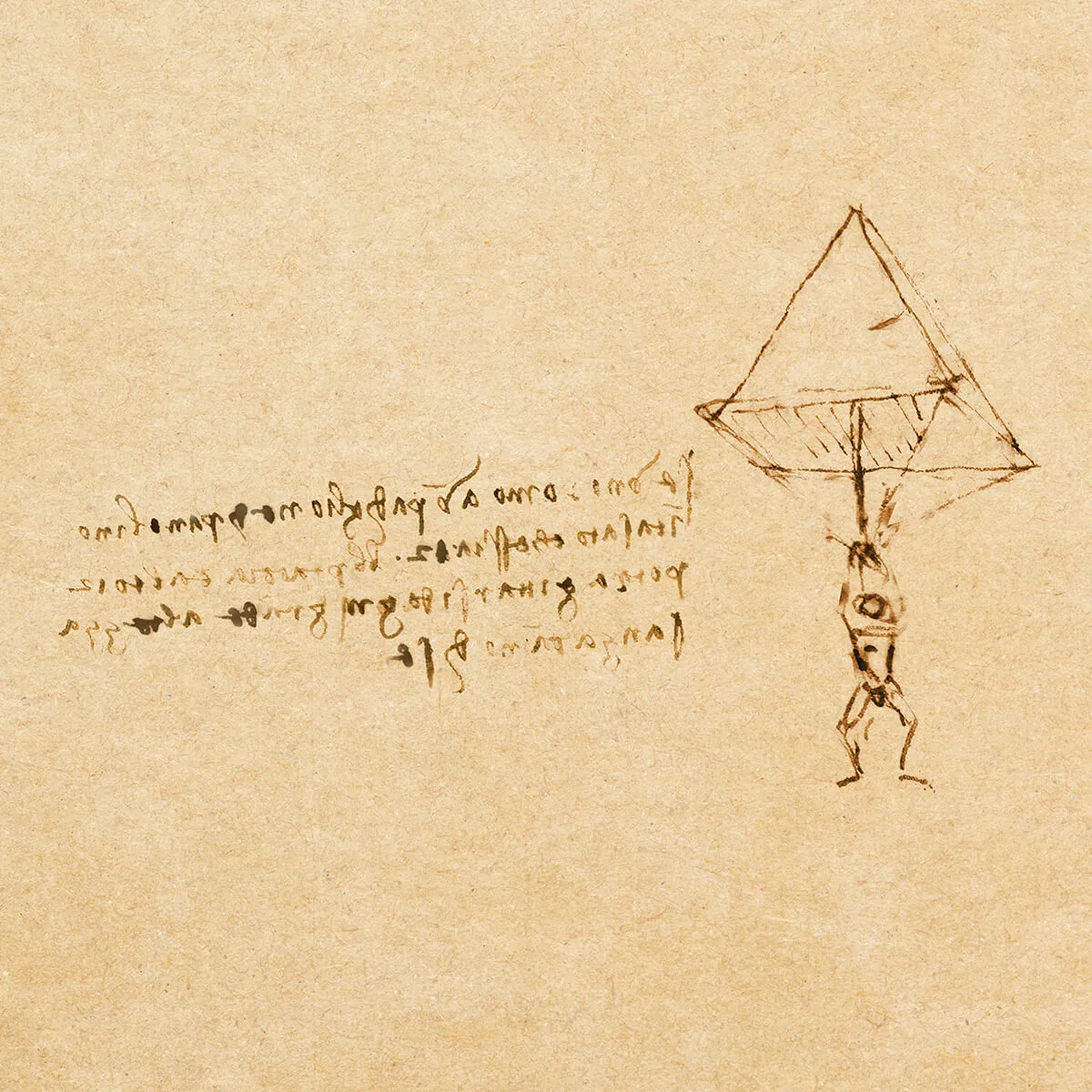

Parachute

Leonardo’s parachute design used a pyramid made of wooden poles, about 7 metres long, to keep a cloth open. Leonardo said, “if a man has a piece of gummed linen cloth that’s 11 metres on each side and 11 metres tall, he can jump from any height without getting hurt.” He saw it as a glider or “flight without wing movement.”

In 2000, a British man named Adrian Nicholas used a replica of this design, made from heavy canvas and wood, to jump from a hot air balloon 3,000 metres (9,800 feet) above the ground. It worked well, but he cut himself free at 600 metres (2,000 feet) and switched to a modern parachute to avoid getting hurt by the heavy pyramid during landing.

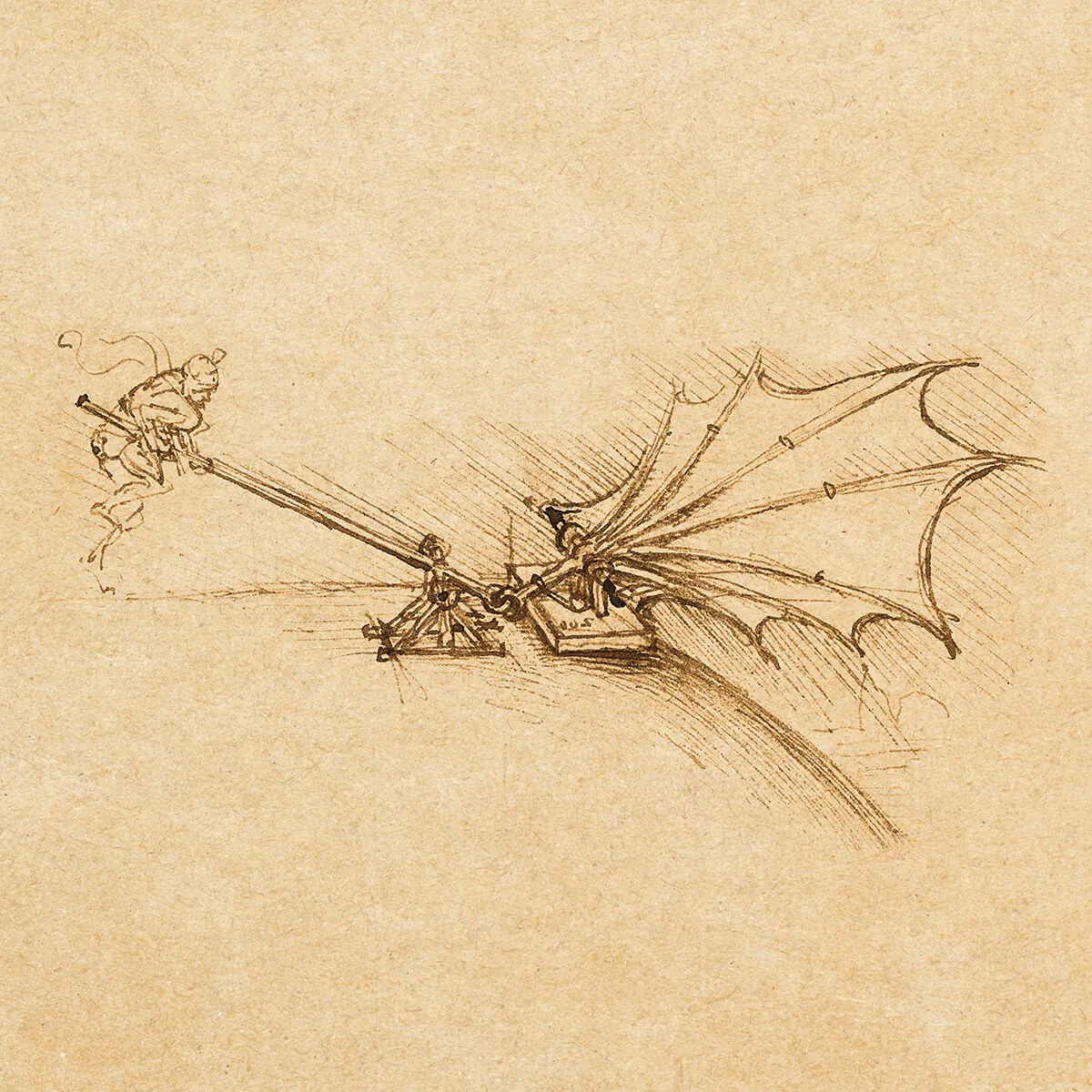

Flapping Wing

This drawing shows an experiment to see if flapping wings could lift a heavy weight. A 12-metre-long wing, made from a frame of cane and covered with paper, was supposed to be attached to a wooden plank weighing as much as a person.

The idea was that if the long lever was pushed down quickly enough, the wing might create enough lift to raise the plank. If this worked, then two wings could lift a pilot and keep them flying.

In his notebook, Leonardo wrote: “... but make sure the force is quick. If this doesn’t work, don’t waste any more time on it.”

Anemometer

This device measures the force of the wind. The swinging lamina (vertical plate) moves like a pointer in the wind, and by reading along the quadrant scale you can determine the strength of the wind conditions.

A similar device was invented by Leon Alberti, an Italian mathematician, in about 1450.

Anemoscope

Among the instruments developed for his flying studies, Leonardo drew this anemoscope that indicated the direction of the wind. It looks exactly like the weather vanes that are often placed on the roof of buildings today.

Speed Gauge for Wind or Water

A question in Leonardo’s mind was, “If the intensity of wind or water remains the same, will five times as much wind or water generate five times more power?”

In this experimental device, wind or water is directed through the two funnel-shaped cones with perforations at the top. The energy source moves the rotating propeller blades on a horizontal shaft, and an attached rope lifts the weight. If the flow of energy through the larger cone is cut off, how far will the weight be lifted by the rotating blades? Will it be lifted five times higher if the smaller cone is blocked off in turn?

Aquatic and Hydraulic Inginuity

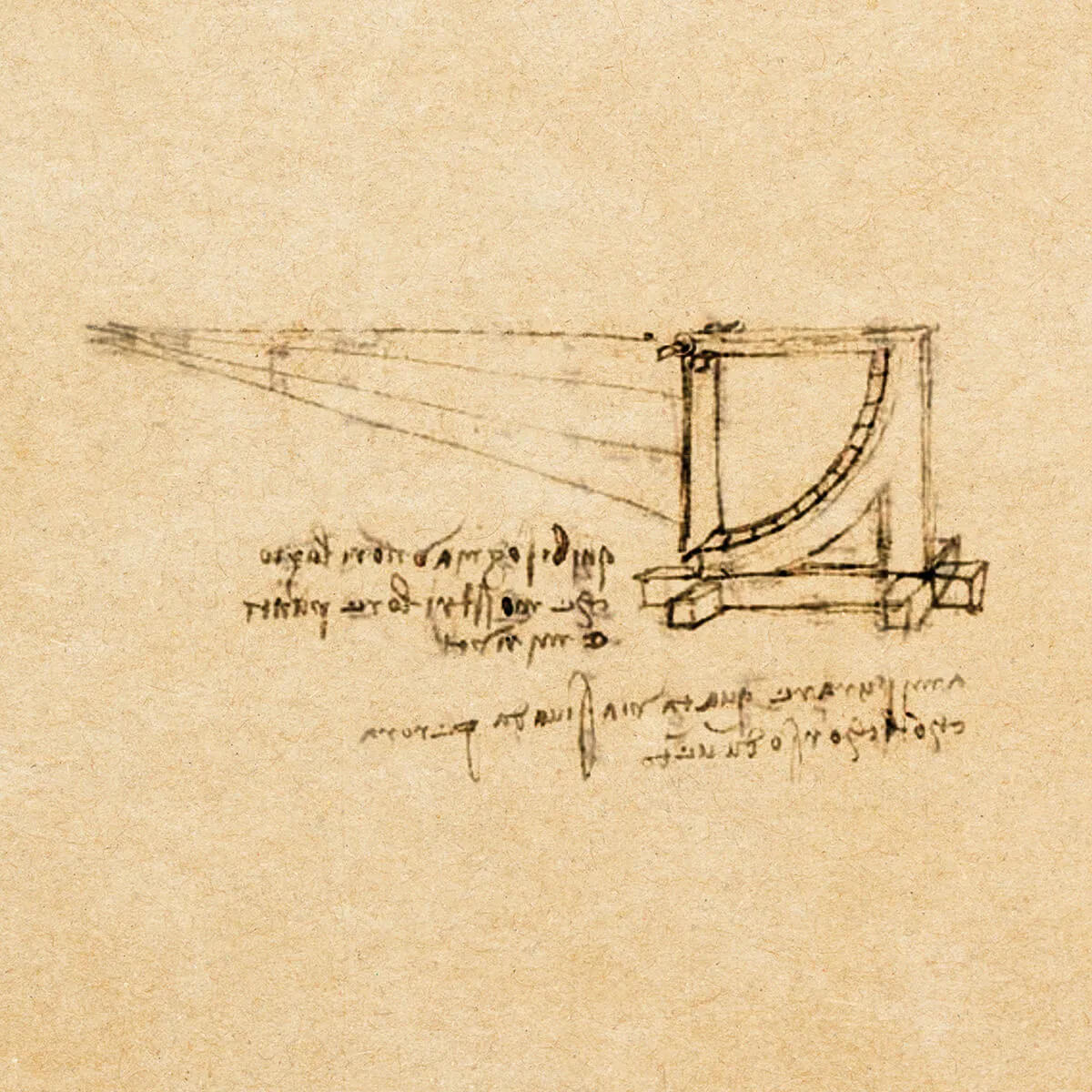

Influenced by the flow of water, Leonardo viewed the sea as the Earth’s ‘lifeblood’ and intensively studied waves and water systems, drawing analogies between water and air.

From the streams, he observed as a child to conceiving hydraulic solutions and boldly proposing innovative plans to tame rivers, control floods, and drain marshes in the inland cities of Florence and Milan.

Leonardo ambitiously attempted a project to divert the Arno River, intending to irrigate the valley around Florence and establish a vital link to the sea. This grand vision was eventually abandoned.

Leonardo’s breadth of innovative hydraulic ideas includes an enhanced Archimedes’ screw for raising and draining water, a hydraulic saw, SCUBA, the diving suit, double-hulled vessels, paddle boats, and the deceptively simple, yet crucial lifebuoy.

Additionally, Leonardo’s visionary sketches showed concepts for a submarine and a system designed to breach the hulls of enemy ships underwater.

“Water is the driving force of all nature.”

– Leonardo da Vinci

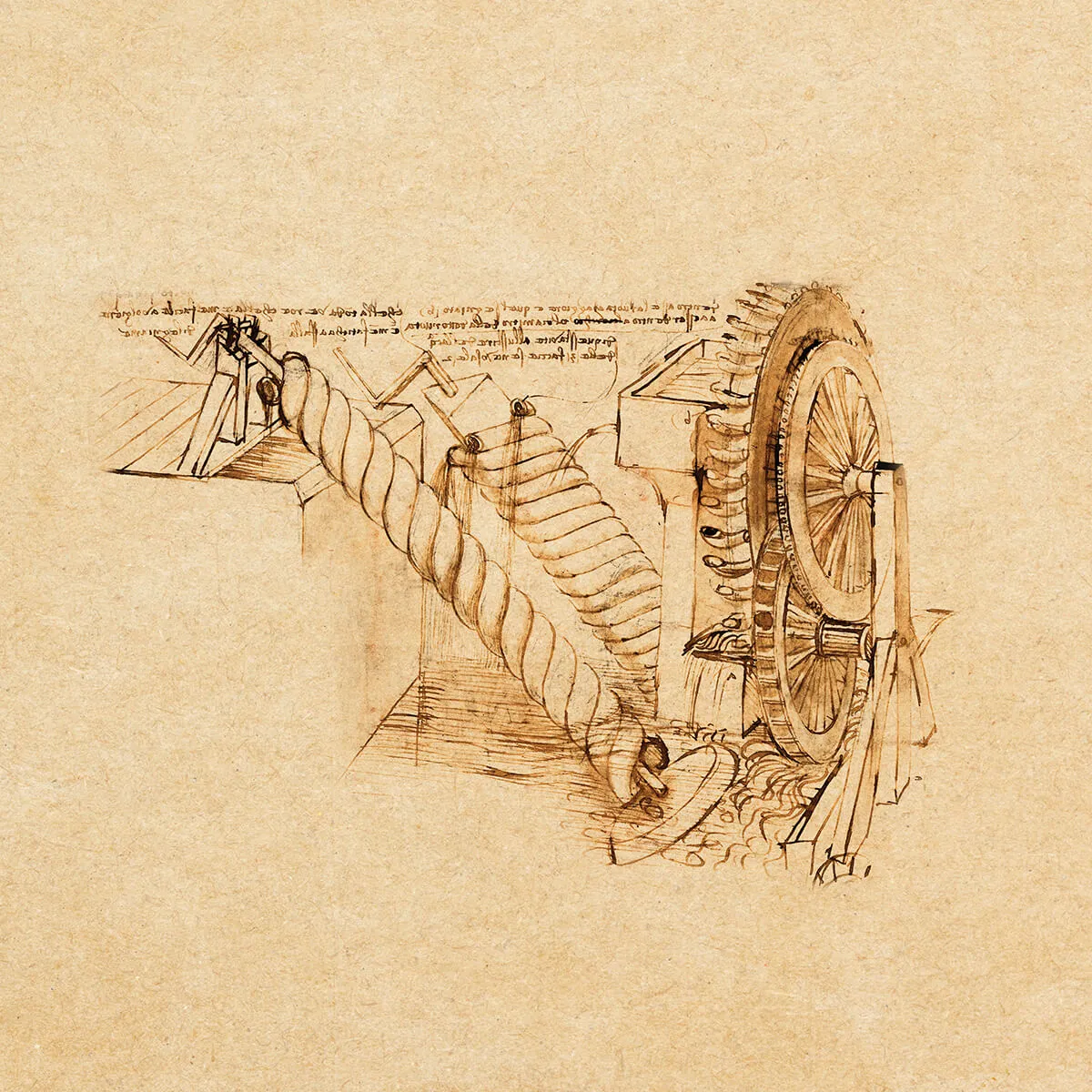

Archimedes’ Screw

This water-lifting machine, which didn’t require much human effort, was well-known in ancient times and it was described by the Greek mathematician Archimedes.

Leonardo created several versions of this machine, proposing different designs and improvements. He considered how the angle of the main axis and the number of coils would affect its efficiency. Leonardo’s main improvement allowed it to lift more water with less spillage. This type of water screw is still used for irrigation and is the basis for many modern industrial pumps.

Emergency Bridge

This bridge was designed for quick setup during battle and was intended to be built by soldiers in emergencies, using small tree trunks from a riverbank.

The trunks are interwoven and secured without ropes or nails. The design ensures that as more weight is applied, the interlocking wood becomes more stable and secure. Leonardo referred to it as a bridge of ‘safety.’

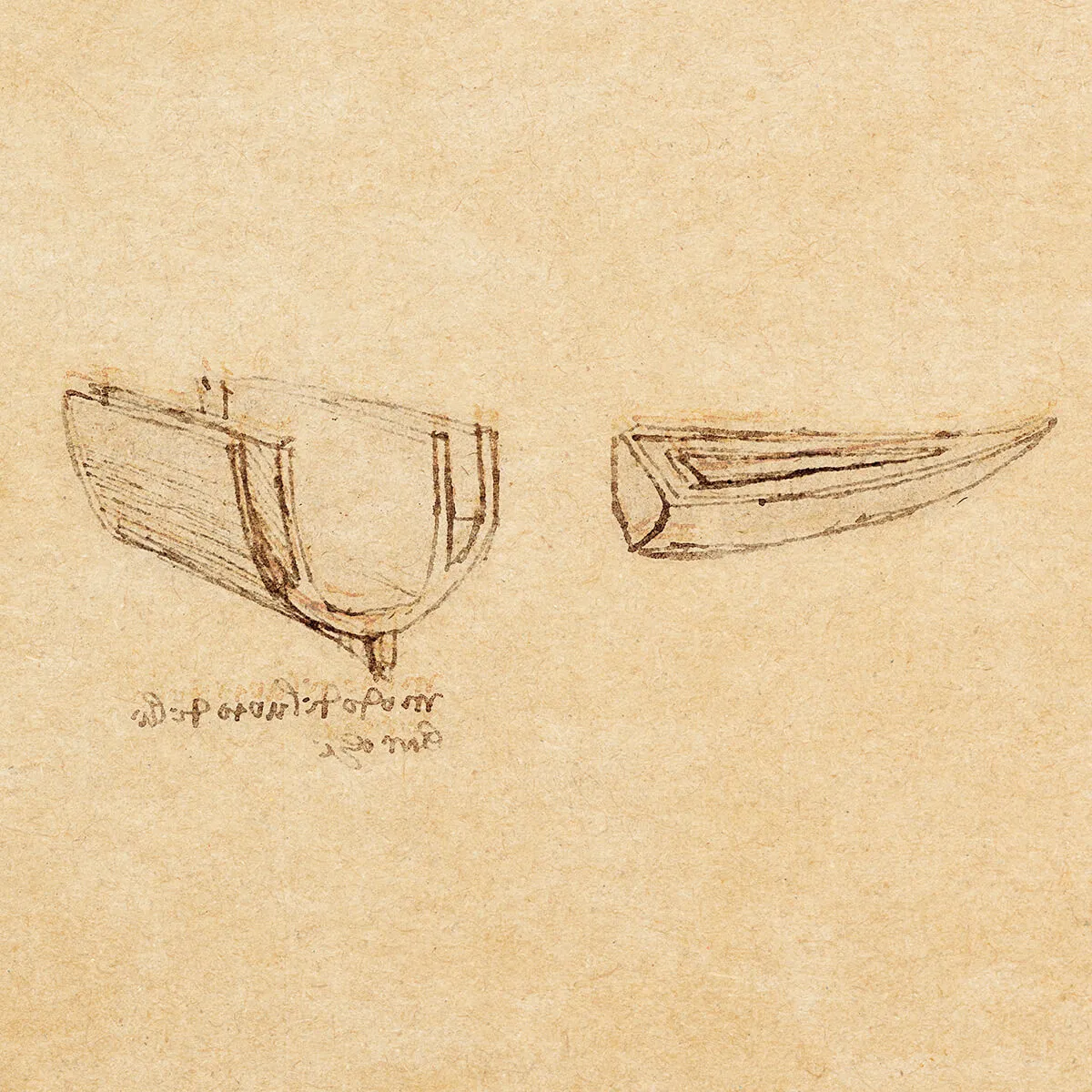

Double-Hulled Ship

Leonardo studied the action of water and the shapes of fish. He drew on these studies to design hulls that were more stable than the round-bottomed ships that were common in his day. He also suggested the idea of a ship with two hulls. If the outer hull was damaged, in war or in an accident at sea, the intact inner hull would keep the ship afloat.

Today, oil tankers generally have a double hull, to increase their safety and protect their load.

Lifebuoy

Leonardo’s note about the drawing says, “How to save your life in the event of a storm and shipwreck.”

The invention is clearly a circular lifebuoy to help keep people afloat.

It was likely from a light bark from cork oak trees, which grew widely around the Mediterranean.

Hand-Flippers

Leonardo created a webbed glove to help people float longer and swim further in the sea. It fastens around the wrist and the glove has five long wooden sticks that extend the fingers, connected by a stretched membrane.

The design mimics the feet of web-footed animals and modern swim flippers are based on a similar concept.

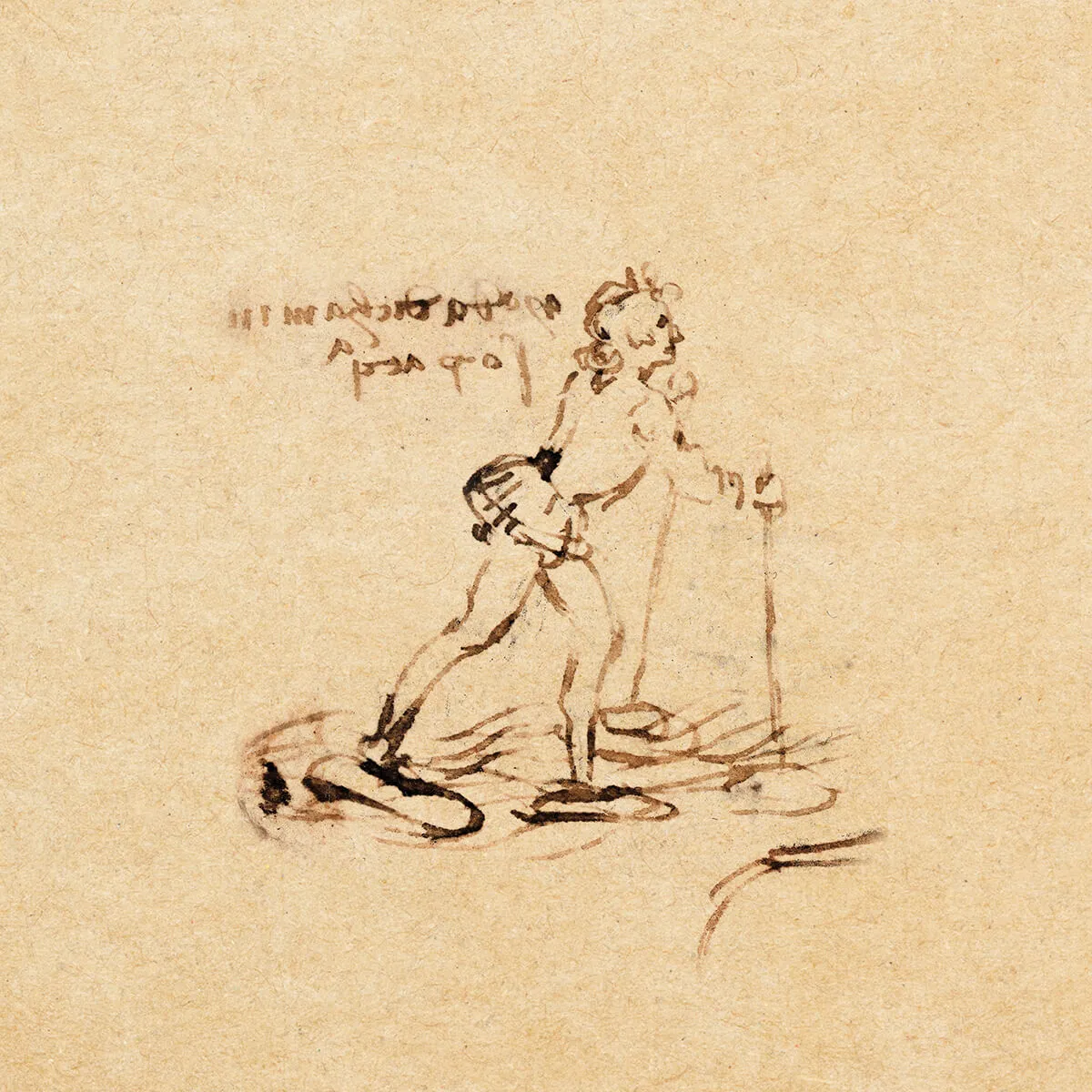

Floats for Walking on Water

Leonardo considered how soldiers could cross shallow water. He proposed strapping inflated leather bags or wineskins to their feet, which, if big enough, would support a soldier’s weight. Wooden planks that float could also help.

He also suggested using two poles with inflated bags at the ends for balance and to help push through the water.

Though Leonardo’s idea wasn’t practical for water, similar concepts are used today by cross-country skiers.

Diving Equipment

Although previous inventors had come up with ways for people to breathe underwater, Leonardo improved on these designs with a watertight leather tunic, strengthened with armour to protect the airbag from being crushed in deep water.

Flexible hoses made of cane, with leather joints reinforced with metal spirals, drew air from above the surface and valves controlled the air intake. The hoses were held up by a floating cork, which acted as a buoy.

Leonardo believed this diving suit could help divers fix hulls underwater or let a group of divers secretly march underwater to attack enemy ships. He suggested this second idea in Venice as a way to defeat the Turkish fleet that was blockading the bay outside the city.

Breathing Equipment

In another design, air tubes connect a face mask to a floating bell-shaped buoy on the surface. The tubes are made of cane, joined with leather, and surrounded by metal rings to prevent them from collapsing under water pressure. Two tubes provide fresh air to the diver, and a valve controls

the airflow.

In 2002, diver Jacquie Cozens tested a diving suit based on this design using pig leather, bamboo tubes, and a cork float. The results were not entirely successful.

Paddle Boat

The quickest way to communicate at that time was by sea and river. Cities like Milan and Florence, which were inland, relied on fast and reliable boats to travel up and down rivers.

Leonardo drew a design for a paddle boat with shovel-shaped paddles, inspired by fish fins. The operator would work two foot pedals. Using reciprocating motion, these pedals would turn the paddle wheels counterclockwise to move the boat forward. Leonardo’s sketches don’t show the entire boat but give hints about how some parts might appear.

.svg)

Exploring the Human Anatomy

The pursuit of anatomical mastery stands as a testament to Leonardo’s unquenchable thirst for knowledge.In his anatomical studies, Leonardo went beyond the surface capturing numerous drawings of the human form in his notebooks.

Documenting the beauty of human proportions and the intricate workings of muscles and tendons in motion led him to dissect and draw over thirty individuals, spanning various ages.

Due to the prohibition of human dissection, Leonardo worked diligently, often in secret, to deepen his understanding.

From capturing the nuances of old age to the vitality of youth, he was the first to identify atherosclerosis, a hardening of the arteries. And his greatest achievement was his discovery of how the aortic valve works, a triumph only confirmed in modern times.

The precision of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings not only served as a cornerstone for understanding the human form but also set the stylistic and formal standards for anatomical drawings, perhaps influencing the iconic textbook Gray’s Anatomy.

Viewing the human body as a marvellously compact machine capable of an extensive array of movements, Leonardo’s profound exploration of anatomical studies proves how far ahead of his time he was.

“The human foot is a masterpiece of engineering and a work of art.”

– Leonardo da Vinci

Resume of a Genius

Even with his remarkable talents, Leonardo needed a source of income. His brilliance attracted commissions from influential figures like the Medici family, Cesare Borgia and Francis I of France.In 1482, he vied for a position under Duke Ludovico Sforza, highlighting his military engineering prowess. Interestingly, he downplayed his artistic gifts in his application. Sforza eventually hired him, though it’s unclear if any military projects materialised.

However, Sforza’s appreciation for Leonardo’s artistry led to the commission of the iconic The Last Supper a decade later.

My Most Illustrious Lord,

Having now sufficiently seen and considered the achievements of all those who count themselves masters and artificers of instruments of war, and having noted that the invention and performance of the said instruments is in no way different from that in common usage, I shall endeavour, while intending no discredit to anyone else, to make myself understood to Your Excellency for the purpose of unfolding to you my secrets, and thereafter offering them at your complete disposal, and when the time is right bringing into effective operation all those things which are in part briefly listed below:

1. I have plans for very light, strong and easily portable bridges with which to pursue and, on some occasions, flee the enemy and others, sturdy and indestructible either by fire or in battle, easy and convenient to lift and place in position. Also means of burning and destroying those of the enemy.

2. I know how, in the course of the siege of a terrain, to remove water from the moats and how to make an infinite number of bridges, mantlets, and scaling ladders and other instruments necessary to such an enterprise.

3. Also, if one cannot, when besieging a terrain, proceed by bombardment either because of the height of the glacis or the strength of its situation and location, I have methods for destroying every fortress or other stranglehold unless it has been founded upon a rock or so forth.

4. I also have types of cannon, most convenient and easily portable, with which to hurl small stones almost like a hail-storm; and the smoke from the cannon will instil a great fear in the enemy on account of the grave damage and confusion.

5. Also, I have means of arriving at a designated spot through mines and secret winding passages constructed completely without noise, even if it should be necessary to pass underneath moats or any river.

6. Also, I will make covered vehicles, safe and unassailable, which will penetrate the enemy and their artillery, and there is no host of armed men so great that they would not break through it. And behind these, the infantry will be able to follow, quite uninjured and unimpeded.

7. Also, should the need arise, I will make cannon, mortar and light ordnance of very beautiful and functional designs that are quite out of the ordinary.

8. Where the use of cannon is impracticable, I will assemble catapults, mangonels, trebuchets and other instruments of wonderful efficiency not in general use. In short, as the variety of circumstances dictate, I will make an infinite number of items for attack and defence.

9. And should a sea battle be occasioned, I have examples of many instruments which are highly suitable either in attack or defence, and craft which will resist the fire of all the heaviest cannon and powder and smoke.

10. In times of peace, I believe I can give as complete satisfaction as any other in the field of architecture and the construction of both public and private buildings, and in conducting water from one place to another.

Also, I can execute sculpture in marble, bronze and clay. Likewise in painting, I can do everything possible as well as any other, whosoever he may be.

Moreover, work could be undertaken on the bronze horse which will be to the immortal glory and eternal honour of the auspicious memory of His Lordship your father, and of the illustrious house of Sforza.

And if any of the above-mentioned things seem impossible or impracticable to anyone, I am most readily disposed to demonstrate them in your park or in whatsoever place shall please Your Excellency, to whom I commend myself with all possible humility.

.svg)

Vitruvian Man: Harmony of Proportions

Based on the writings of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, Vitruvian Man demonstrates the ‘golden ratio,’ or perfect proportions of the human body.

A man, in two superimposed positions with outstretched limbs, fits perfectly within both the square and the circle highlighting the inherent balance and symmetry of the human form.

For Leonardo, understanding the proportions of the body with accuracy was essential for creating representations of the human body in art and architecture.

Vitruvian Man reflects Leonardo’s dedication to understanding the mathematical relationships governing the human body and serves as a visual expression of the ideal proportions according to Vitruvian principles.

A replica of Vitruvian Man is on display with an interactive experience to see how close you are to ‘Divine Proportion’.

“Learn how to see. Realise that everything connects to everything else.”

– Leonardo da Vinci

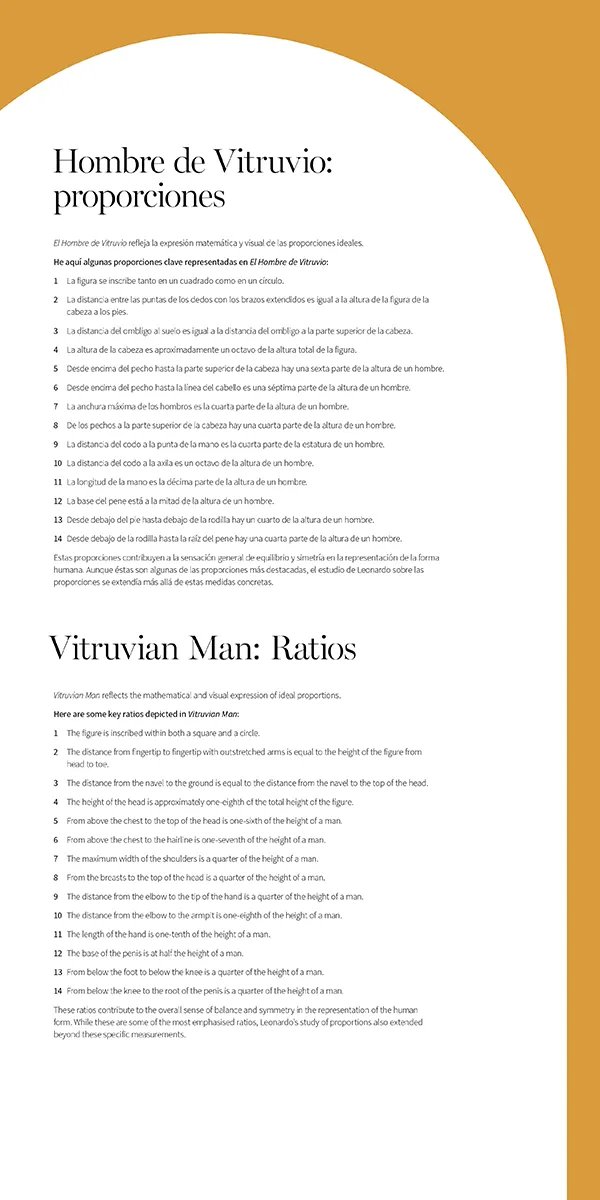

Vitruvian Man: Ratios

Vitruvian Man reflects the mathematical and visual expression of ideal proportions. Here are some key ratios depicted in Vitruvian Man:

1. The figure is inscribed within both a square and a circle.

2. The distance from fingertip to fingertip with outstretched arms is equal to the height of the figure from head to toe.

3. The distance from the navel to the ground is equal to the distance from the navel to the top of the head.

4. The height of the head is approximately one-eighth of the total height of the figure.

5. From above the chest to the top of the head is one-sixth of the height of a man.

6. From above the chest to the hairline is one-seventh of the height of a man.

7. The maximum width of the shoulders is a quarter of the height of a man.

8. From the breasts to the top of the head is a quarter of the height of a man.

9. The distance from the elbow to the tip of the hand is a quarter of the height of a man.

10. The distance from the elbow to the armpit is one-eighth of the height of a man.

11. The length of the hand is one-tenth of the height of a man.

12. The base of the penis is at half the height of a man.

13. From below the foot to below the knee is a quarter of the height of a man.

14. From below the knee to the root of the penis is a quarter of the height of a man.

These ratios contribute to the overall sense of balance and symmetry in the representation of the human form. While these are some of the most emphasised ratios, Leonardo’s study of proportions also extended beyond these specific measurements.

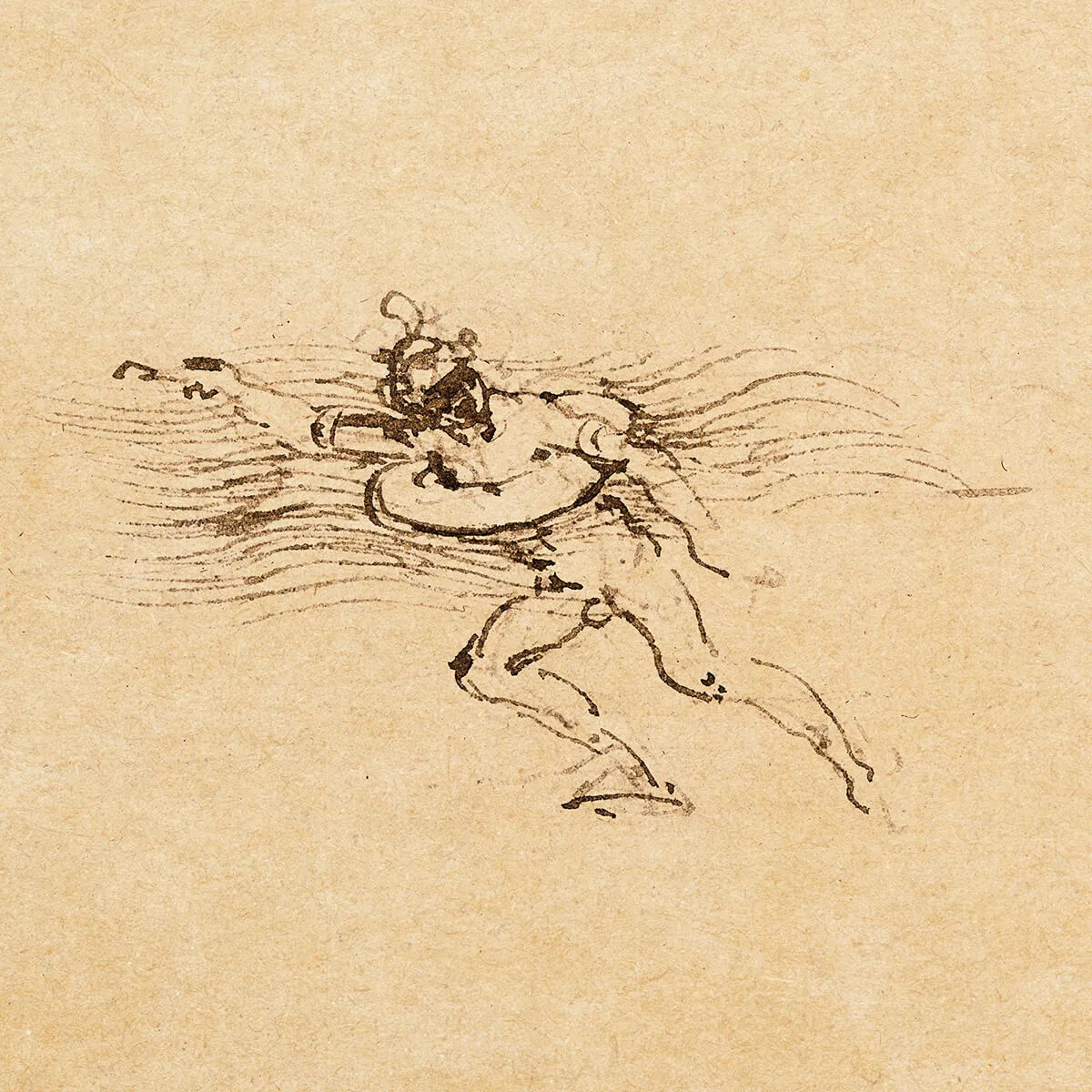

Dynamics of Nature

The movement of water. The flow of air. The interplay of light. Leonardo's drawings of swirling water, air currents, and shadows show his desire to understand how the universe works physically and mechanically.

Central to his enquiries was the question: what hidden mechanisms govern the essence of life itself?

Leonardo studied how anatomy and behaviour are connected in both animals and people, thinking deeply about how expressions show both physical and emotional feelings. He envisioned a union between human actions, natural forces, and the creation of machines that mirrored the patterns found in nature.

From flywheels to ball bearing systems, coil springs, motion transformations, and the eccentric cam, each invention reflects Leonardo’s dedication to unravelling the intricacies of mechanical principles and applying this knowledge to the tangible world.

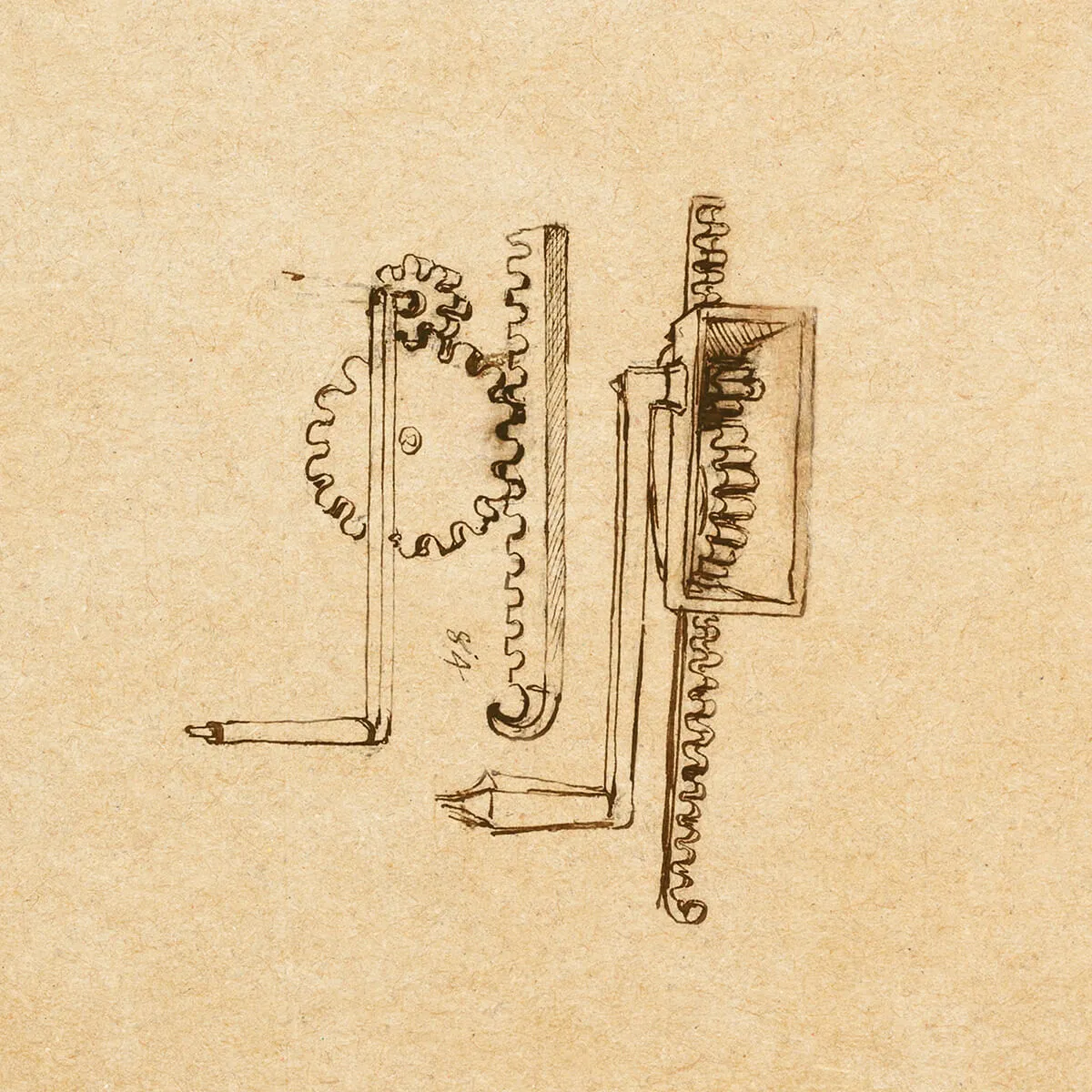

Jack

This simple rack and pinion system is the basis for today’s car jacks. It changes circular motion into straight-line motion, making it possible to lift heavy objects with little effort.

Here’s how it works: a crank turns a small gear wheel, which engages with the teeth on a straight rack, causing it to move upward. Anything on the rack is lifted as it moves. To lower the object, you just turn the crank in the opposite direction.

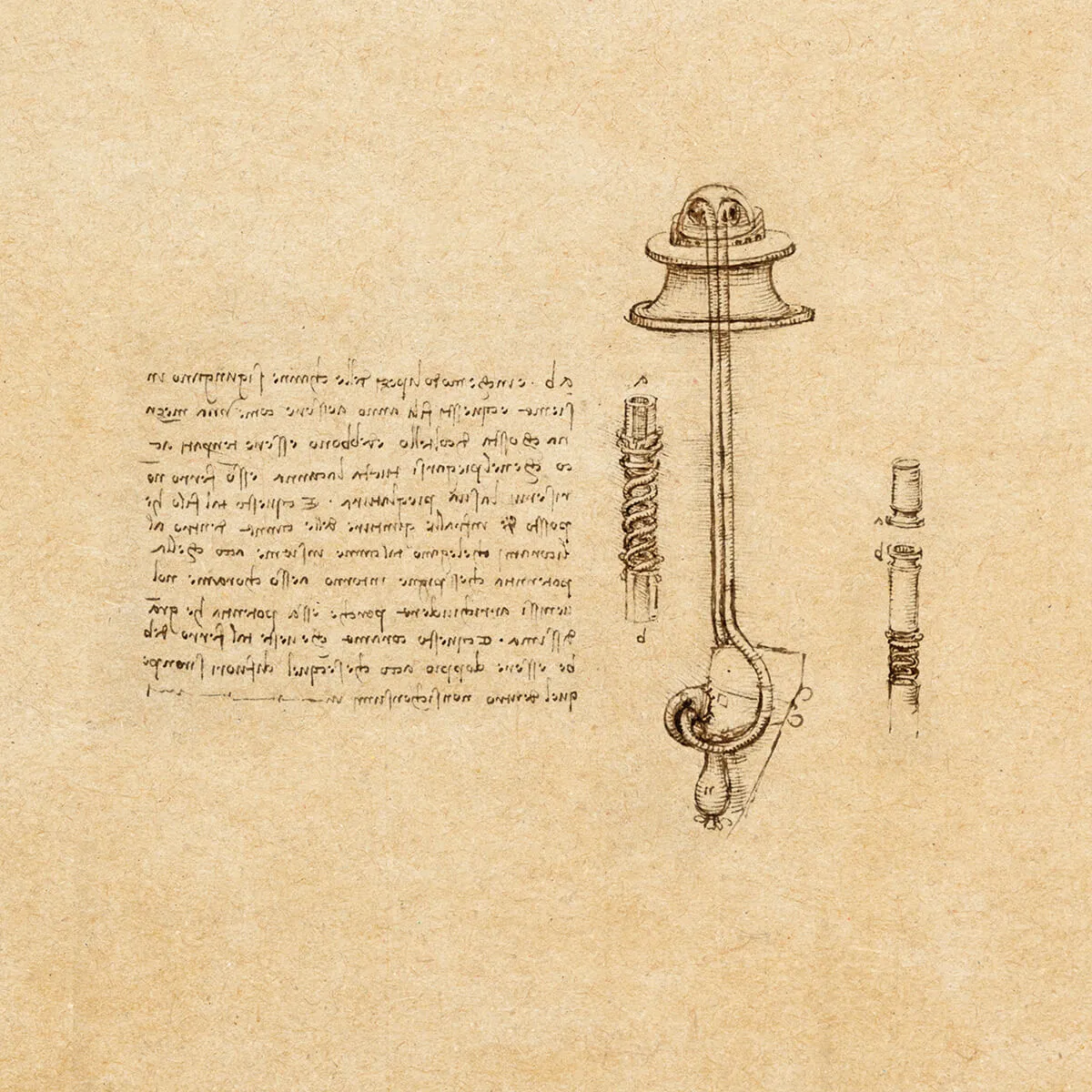

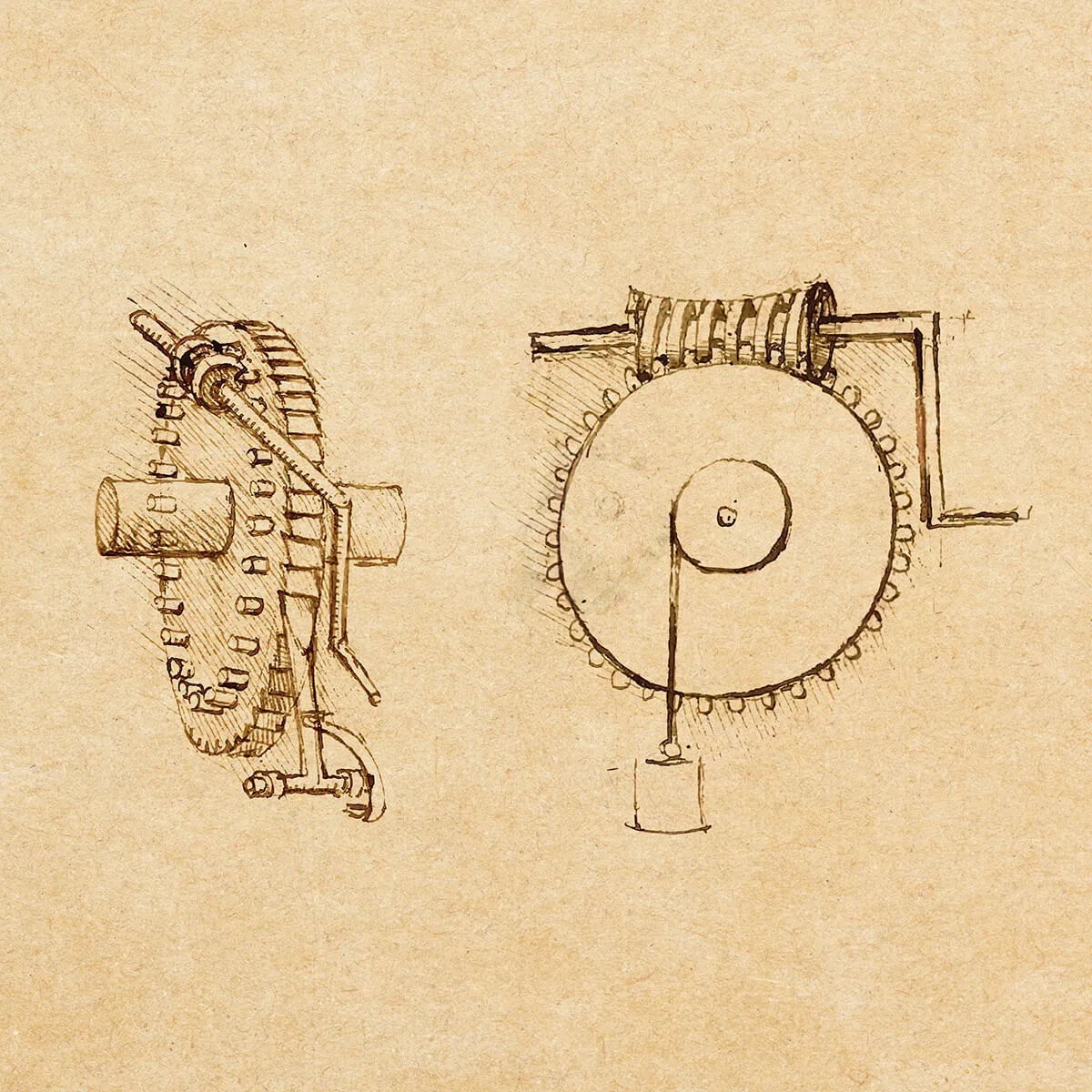

Helicoidal Mechanism

This mechanical system for transmitting rotary motion often appears in Leonardo’s designs.

The endless screw at the top makes contact with the gear wheel over the entire arc of the wheel, not just at one spot. Because it catches many of the wheel cogs at one time, it distributes the force over a wider area and reduces the risk of failure if a cog breaks under the strain.

Leonardo was further developing the principles of Archimedes’ screw. This device has a range of contemporary applications where smoothness of transmission is required.

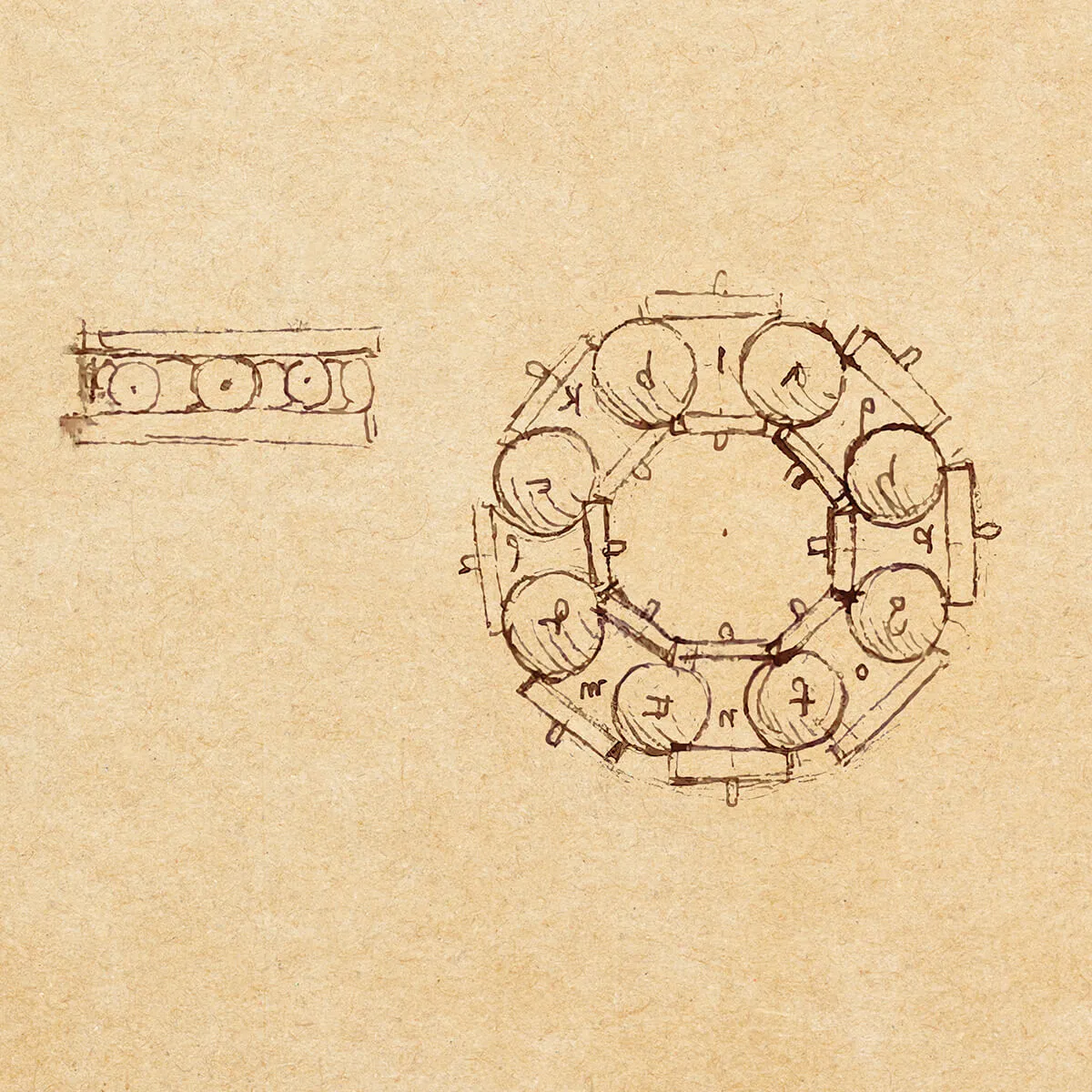

Rolling Ball Bearings

Leonardo understood the concept of using ball bearings to reduce friction. In his design, three spherical balls rest in a curved base, allowing them to move freely.

These balls help distribute the friction caused by a vertical shaft’s pressure. Leonardo noted that three balls work best; adding a fourth would create uneven movement and increase resistance, making the system less effective.

This idea, like many of Leonardo’s inventions, was lost to time. It wasn’t until 1791 that a carriage-maker in Wales patented a similar concept.

Flywheels

A flywheel is a mechanical device that helps keep rotation speed steady. In Leonardo’s design, turning the crank quickly causes four spheres to rise due to centrifugal force until they become horizontal with their chains. When the balls and the shaft reach their maximum spinning speed, they rotate at a consistent rate.

The flywheel stores energy and reduces the effort needed to keep it moving. It also helps maintain a steady rotation when the shaft experiences changes in pressure. The basic concept was already known to Leonardo, like in a potter’s wheel.

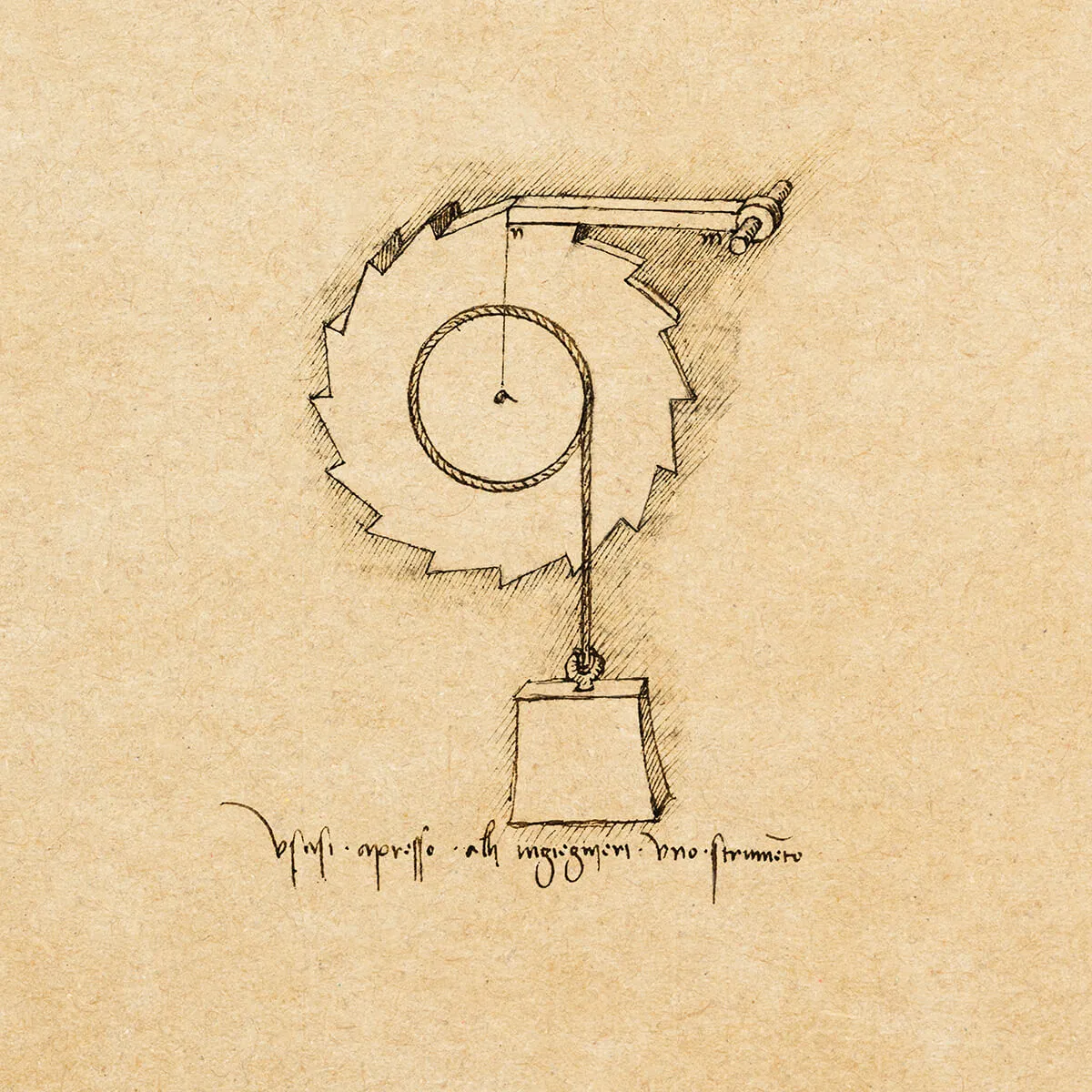

Automatic Blocking Mechanism

When lifting heavy weights in mechanical processes, it’s crucial to prevent the lifting wheel from spinning uncontrollably if something goes wrong.

Leonardo explored different locking systems to stop the wheel from rotating in the wrong direction while a weight is being lifted. The catch pushes against a cog on the wheel, stopping it from turning backwards and dropping the weight.

This concept, initially used for loading catapults, is the basis for the ratchet-locking mechanisms used today.

Hammer Driven by an Eccentric Cam

Leonardo frequently uses rotating cams, which are wheels with shaped bumps, to create various mechanical movements. In this machine, turning the cam with a crank makes the bumps convert circular motion into up-and-down motion. The cam lifts a hammer, and when it drops, it strikes the same spot every time with its full weight.

This mechanism could have been designed to aid blacksmiths who use hammers and anvils to shape swords, horseshoes, and other metal tools.

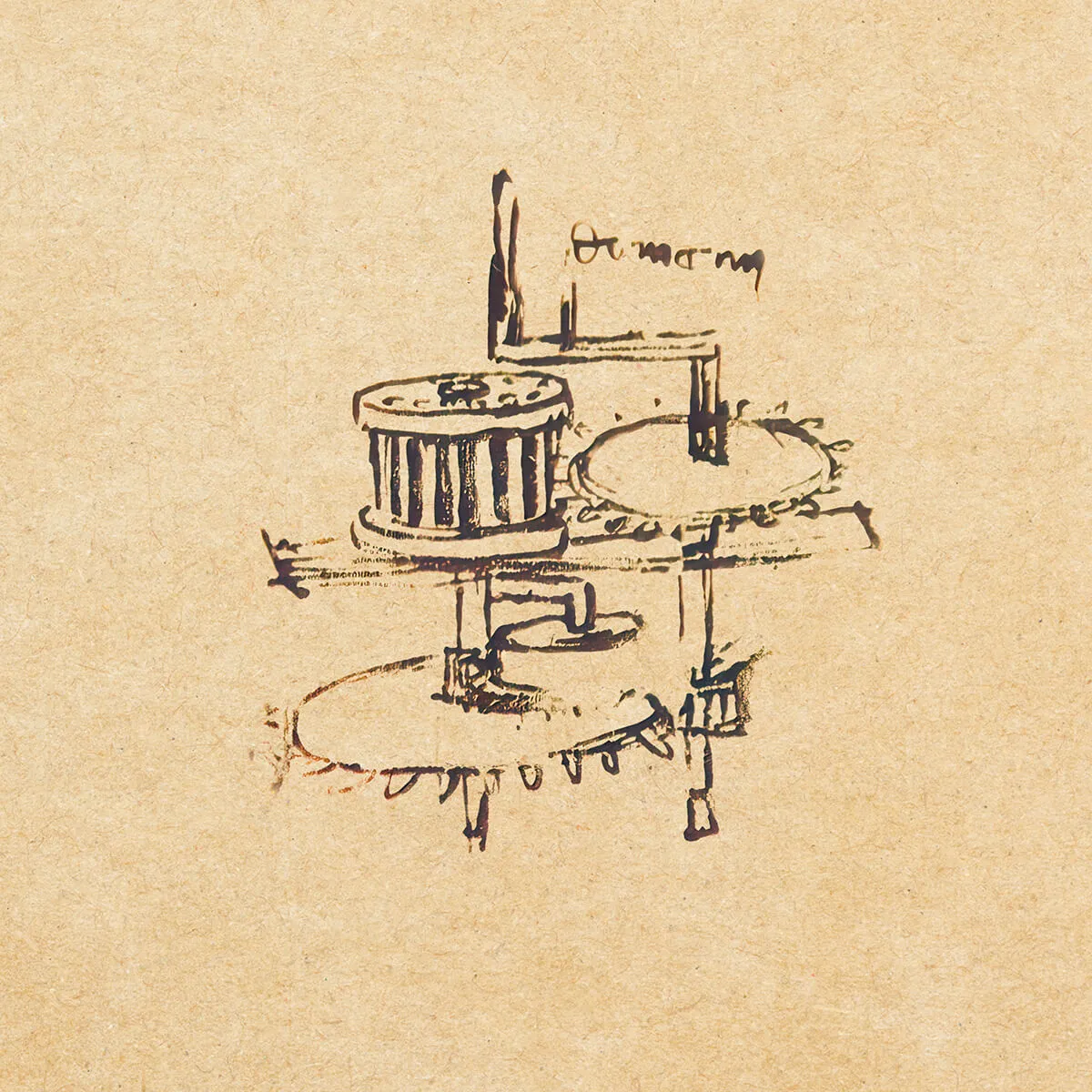

Cog-Wheels Lantern Mechanism

The gearwheel, invented by Archimedes in the third century B.C., was familiar in Leonardo’s era. Leonardo worked on improving various gears that transmit motion and force. One common design he used involved a combination of a gearwheel and a lantern pinion.

A lantern pinion consists of small cylinders held between two discs. The gear wheel has a disc with vertical pins spaced evenly around its edge. It transfers motion when the lantern, rotated by a crank, engages with these pins and moves the gearwheel. In another design, the crank turns the gearwheel directly. Modern clocks still use similar mechanisms.

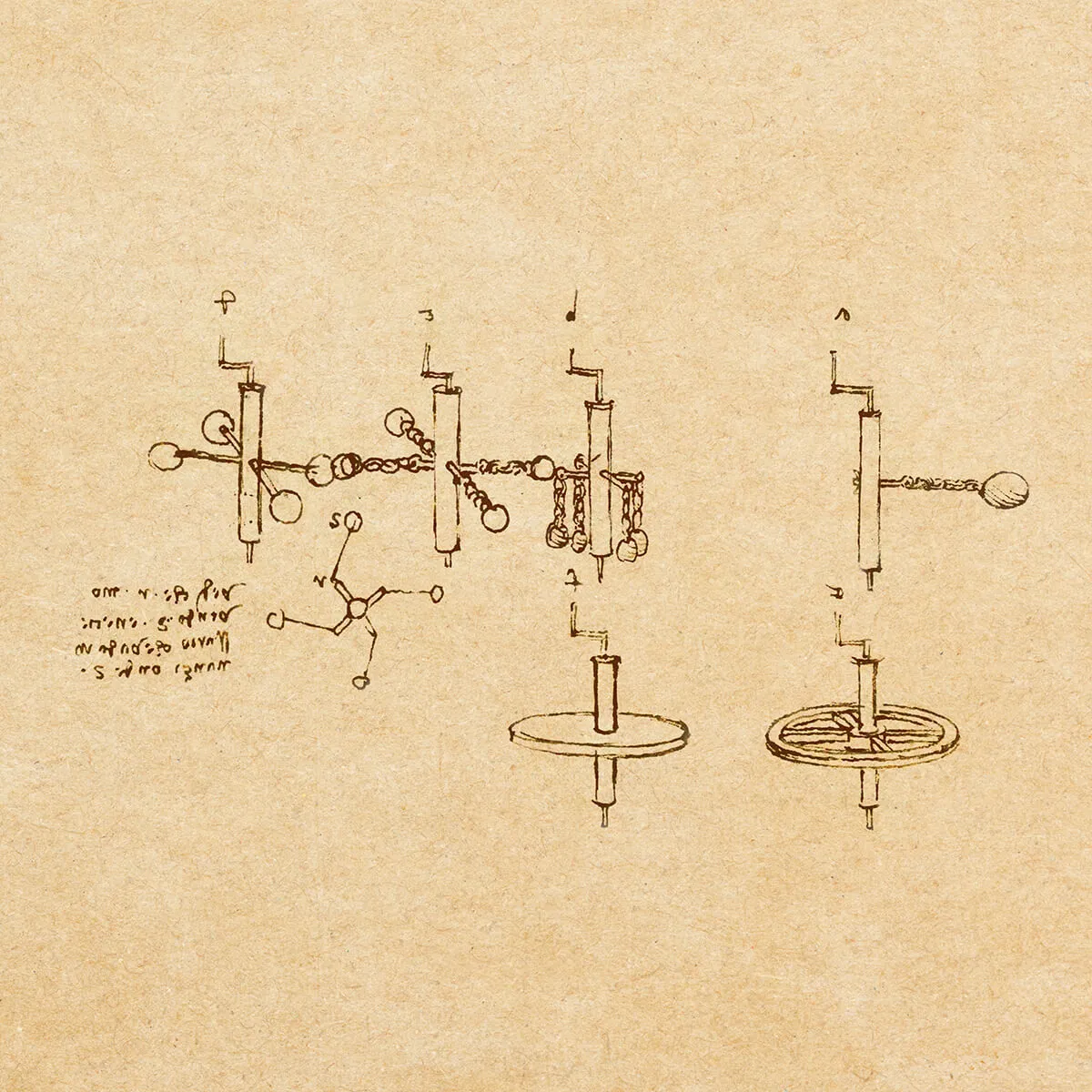

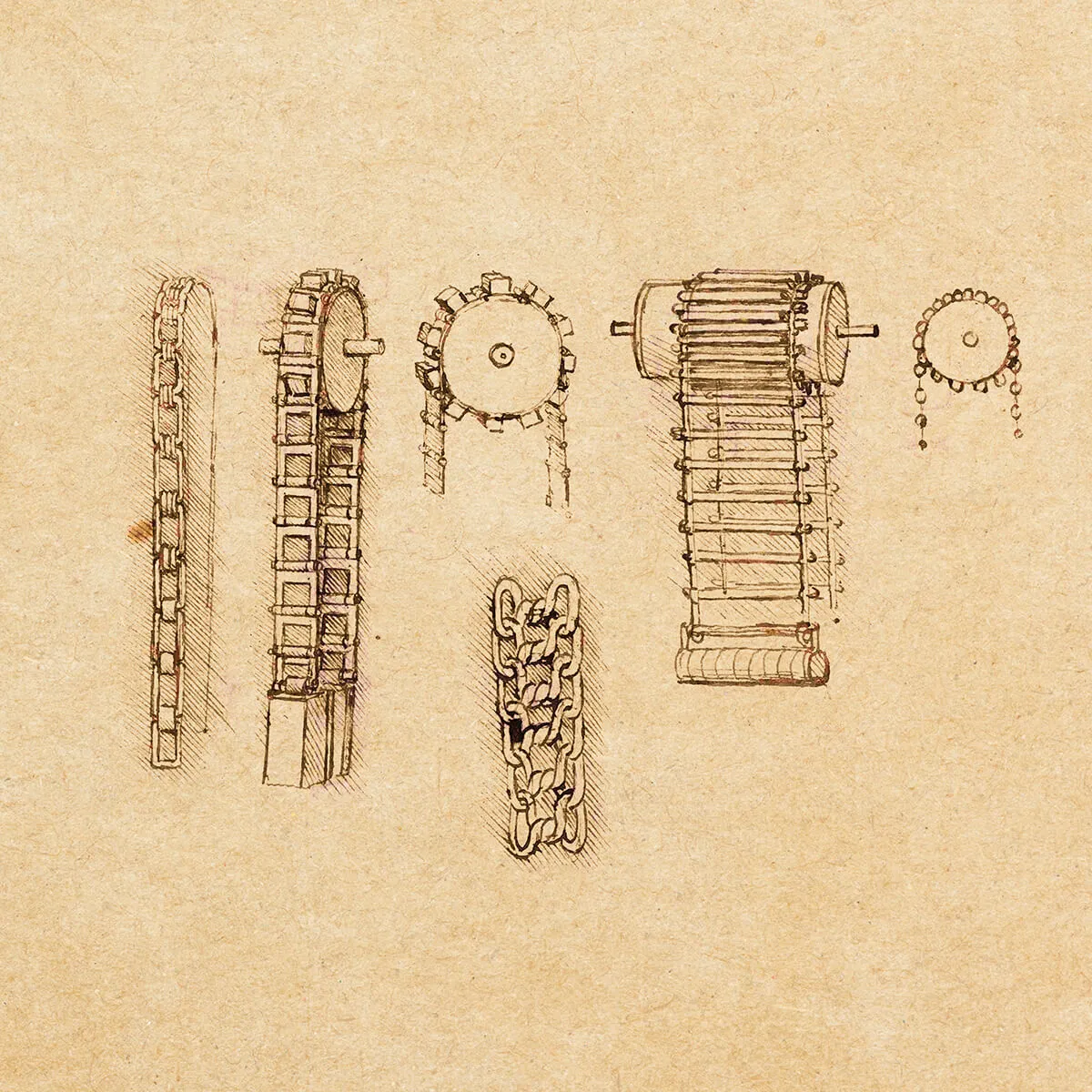

Chain Crankcase

Leonardo was very interested in the mechanics of rotating motion. In this study, he explores using chains instead of ropes. This mechanical setup uses two toothed wheels connected by a chain, maintaining a fixed distance and alignment, either vertically or horizontally. Compared to ropes, this chain system is more efficient and safer when moving heavy loads.

Additionally, this setup can create the back-and-forth motion needed in clock mechanisms.

.svg)

Musical Instruments and Optics

Music held second position to painting among the creative arts, earning Leonardo respect as a musician.

Gifted with a beautiful singing voice, Leonardo showed great skill in playing the lira da braccio, a precursor to the modern violin. The majority of his writings on music have unfortunately been lost.

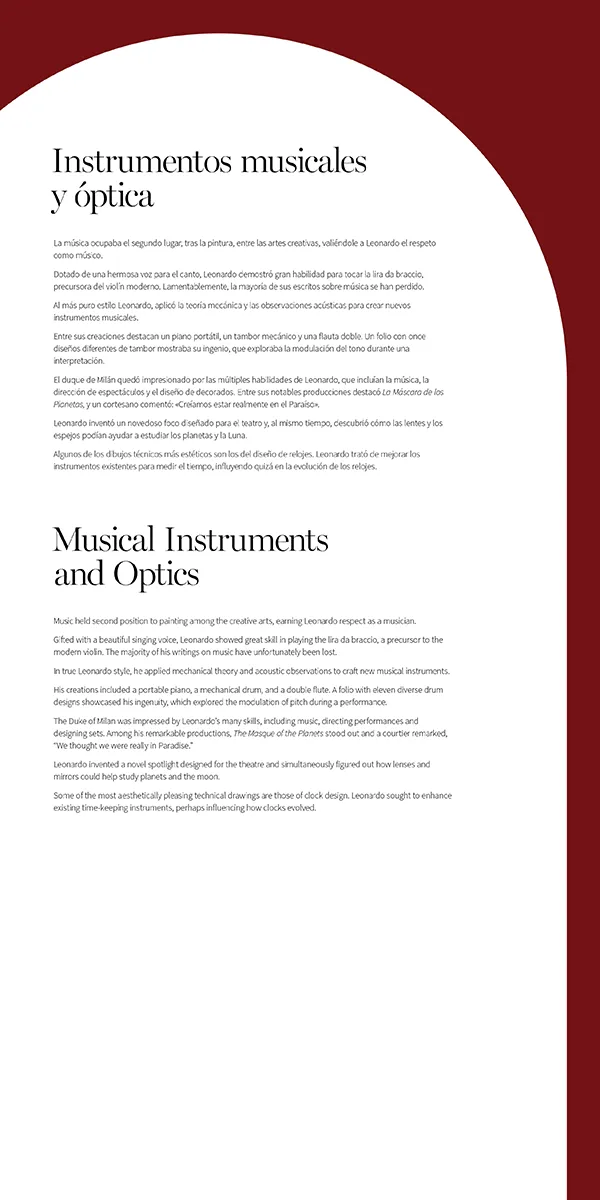

In true Leonardo style, he applied mechanical theory and acoustic observations to craft new musical instruments.

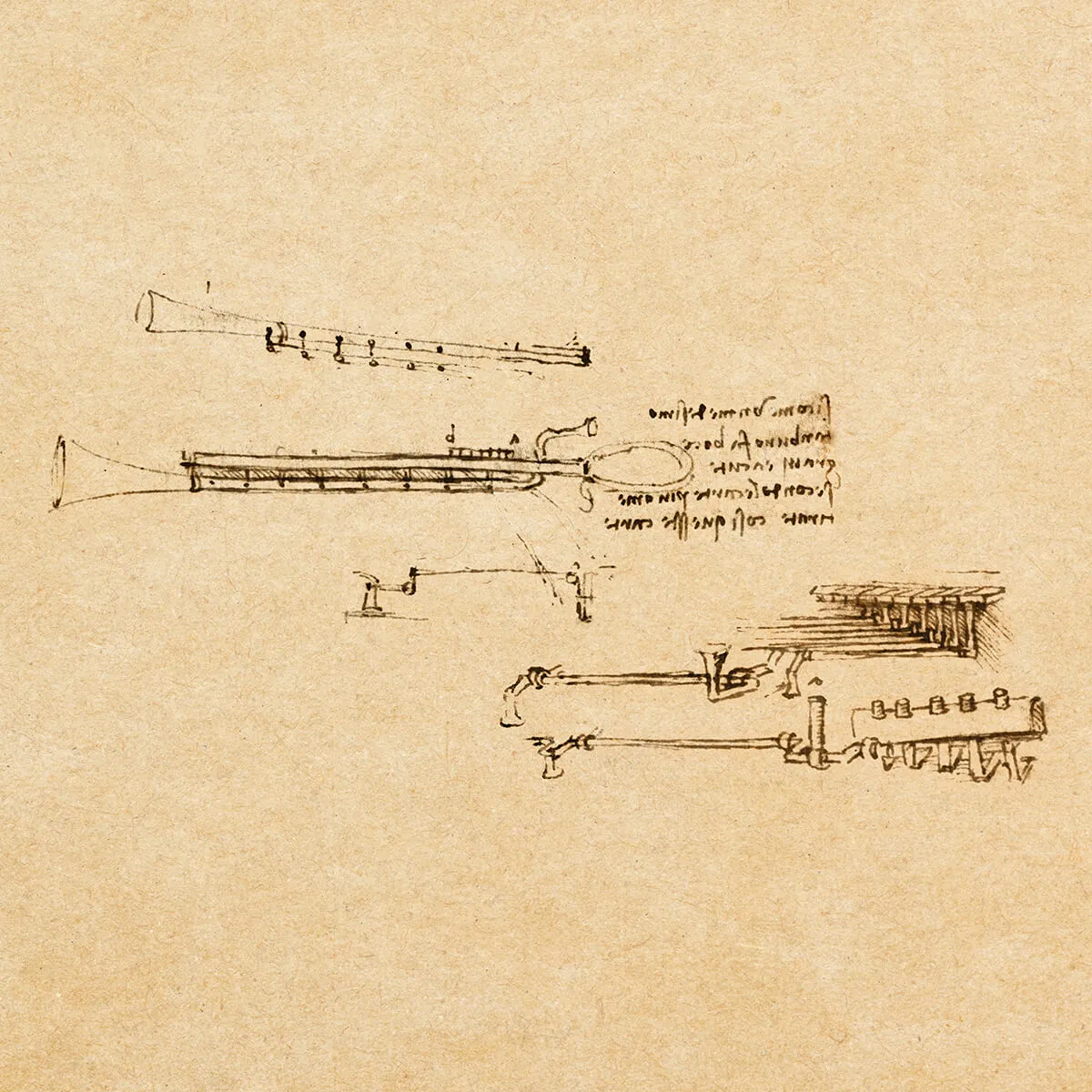

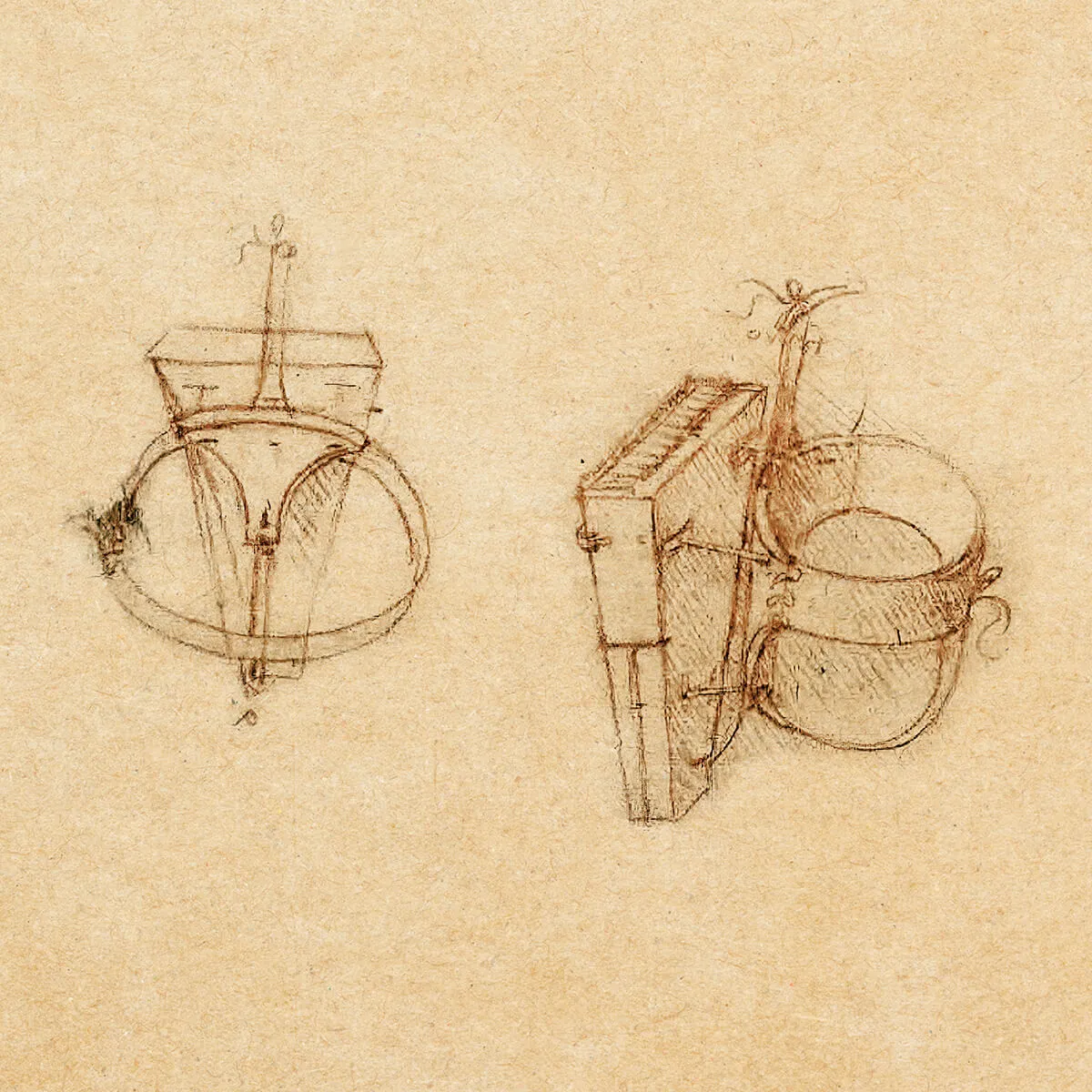

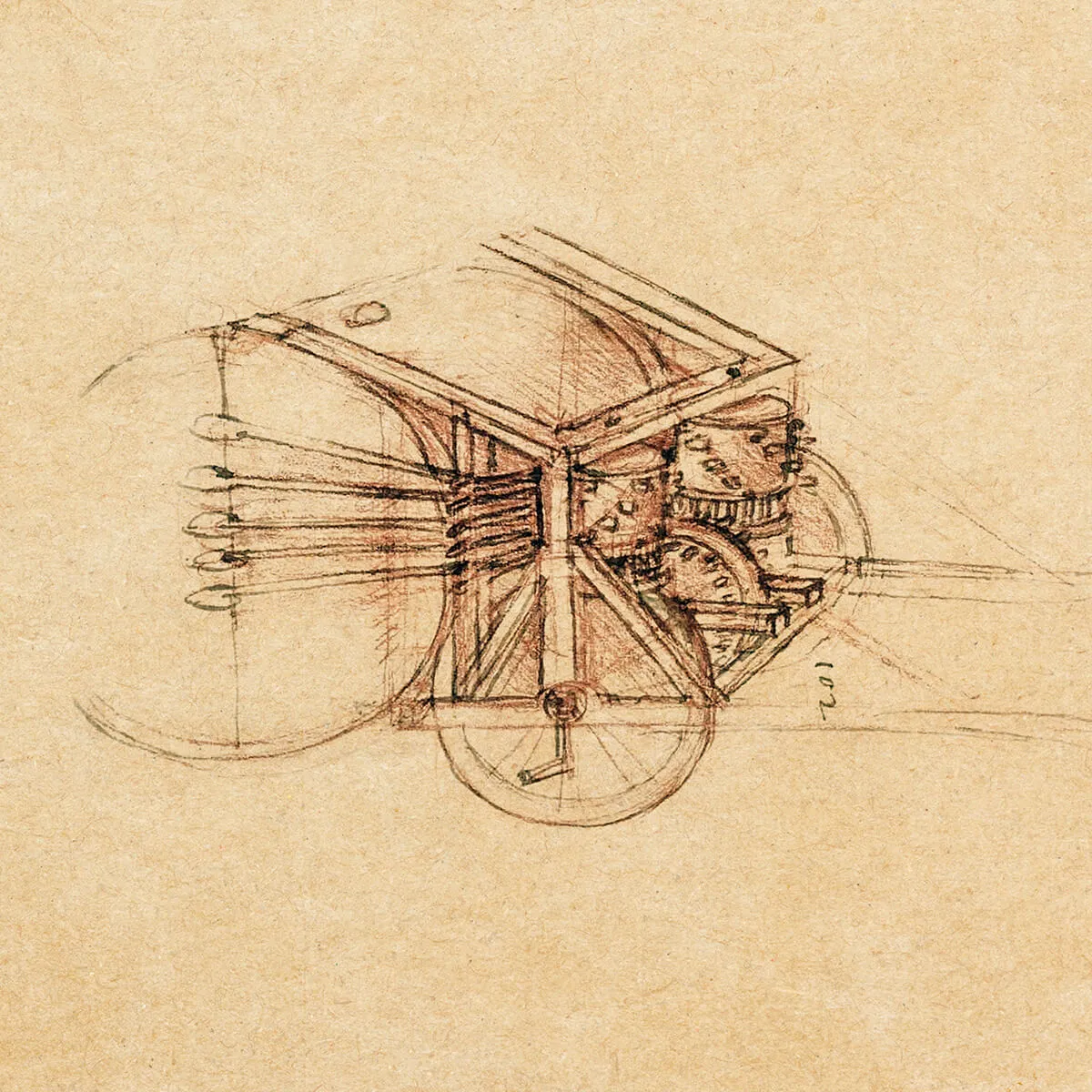

His creations included a portable piano, a mechanical drum, and a double flute. A folio with eleven diverse drum designs showcased his ingenuity, which explored the modulation of pitch during a performance.

The Duke of Milan was impressed by Leonardo’s many skills, including music, directing performances and designing sets. Among his remarkable productions, The Masque of the Planets stood out and a courtier remarked, “We thought we were really in Paradise.”

Leonardo invented a novel spotlight designed for the theatre and simultaneously figured out how lenses and mirrors could help study planets and the moon.

Some of the most aesthetically pleasing technical drawings are those of clock design. Leonardo sought to enhance existing time-keeping instruments, perhaps influencing how clocks evolved.

Mirrors Room

Have you ever stood between two mirrors facing each other and noticed how your reflection appears to repeat and shrink with each step further? The first reflection shows your usual size, but the second and subsequent reflections appear smaller.

Leonardo described an eight-sided room where each wall was a flat mirror. He noted that standing in this space allowed a person to see themselves countless times. Leonardo might have used a similar setup in his studio, peering through a hole with his right eye to observe his subject, while painting freely with his left hand.

Costume Designer

While working for the Duke of Milan, Leonardo was in charge of organising many lavish events. During these famous celebrations, he took on multiple roles, including inventor, music composer, costume designer, stage manager, and producer.

Leonardo’s work involved creating complex costumes, masks, and mechanical devices, all designed to impress and entertain the guests. These elaborate gatherings were not only for fun, they also demonstrated Ludovico’s prestige and power. As Leonardo’s events became more successful, his standing with the Duke grew stronger.

Double Flute

Leonardo, a skilled musician, enhanced various musical instruments by making them more automatic, easier to play, and adding new sound effects.

For the flute, he added keys and finger holes along its length to improve its design. These wind instrument designs were created for court performances celebrating the marriage of the Duke of Milan’s nephew to Isabella of Aragon in 1490.

Portable Piano

Leonardo produced many sketches and projects for musical instruments. This folio shows the workings of a portable instrument. In the centre of the page at the bottom, there is a drawing of the instrument’s case, showing how it is worn around the waist and played with both hands, like a piano.

Inside there is a continuously-moving horsehair bow that is operated via a system of pulleys and a flywheel as the player walks along. A complex system of cams and pulleys move the strings across the bow; a sound similar to that of a viola is produced. It has a range of three octaves.

Mechanical Drum

Leonardo designed mechanical drums for military marches, potentially used when soldiers entered battle.

The drums played complex rhythms based on the movement of the wagon’s axle. As the cart was pulled, gears turned two central rollers, moving the ten drumsticks (five on each side).

By adjusting the pegs or cams on the rollers, the beat and rhythm could be changed. The loud sound from these drums could make an approaching army seem larger than it was, possibly intimidating the enemy.

.svg)

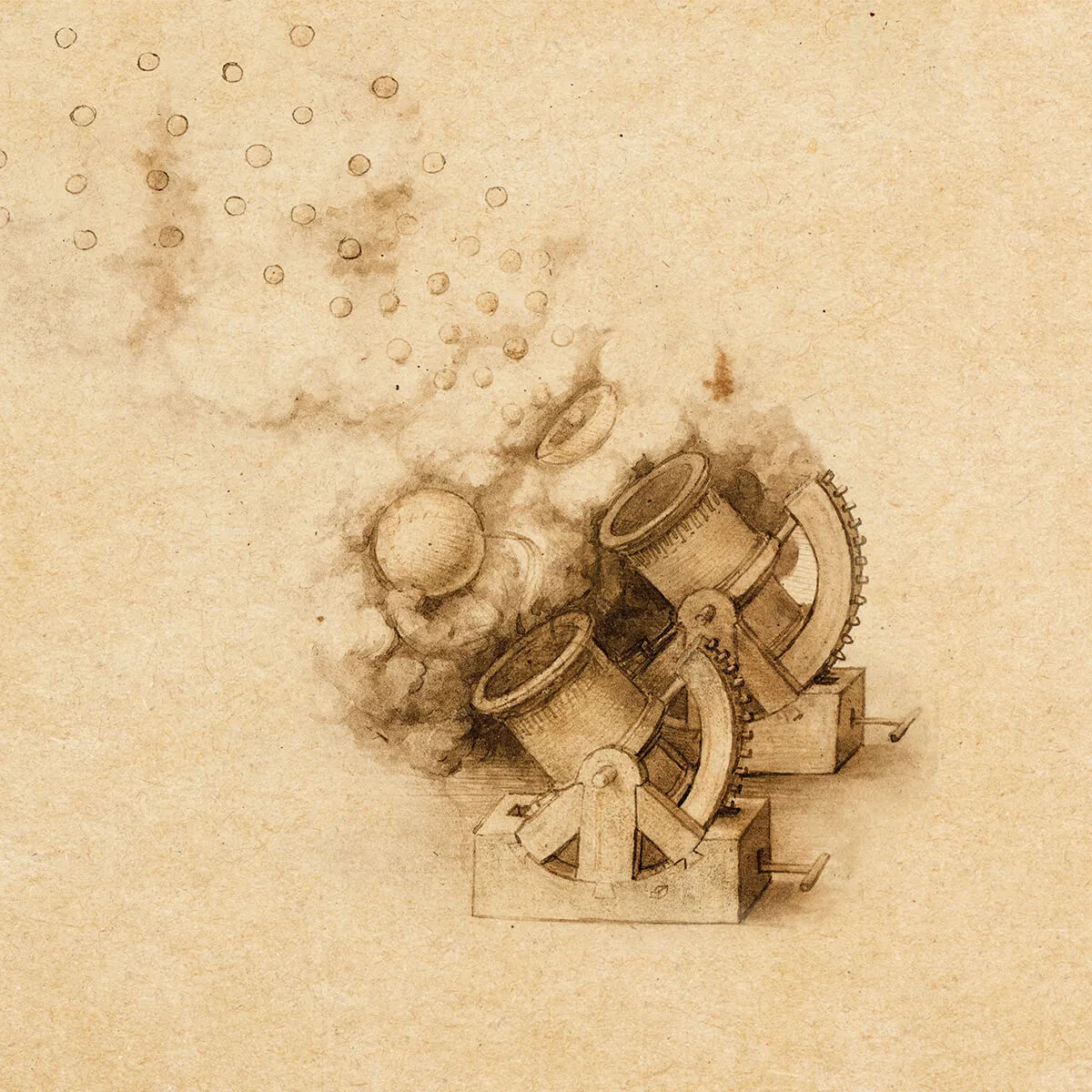

Military Engineering Exploits

Despite being a known pacifist, Leonardo recognised the reality that his wealthy patrons valued military machines over paintings. Embracing the challenge directing his intellect towards the creation of powerful weapons of war.

During times of conflict both internally within Italian cities and externally with foes like the French, Leonardo became a strategic advisor giving him income and time to pursue his scientific studies.

Between 1483 and 1490, Leonardo focused on designing war machines while living in Milan. He later continued his military innovation work while living in Florence.

Although his designs were initially straightforward, over time each design showcased his deep understanding of changing warfare dynamics and the need for clever solutions.

Leonardo innovated a range of warfare artillery including bridges, assault ladders, artillery, gun carriages, multi-barrelled machine guns, cannons, catapults, giant crossbows, armoured cars, and more.

Beyond weapons, Leonardo was fascinated by the colossal war horses owned by nobles and knights. Captivated by the strength and beauty of horses, his exquisite sketches immortalised these majestic creatures.

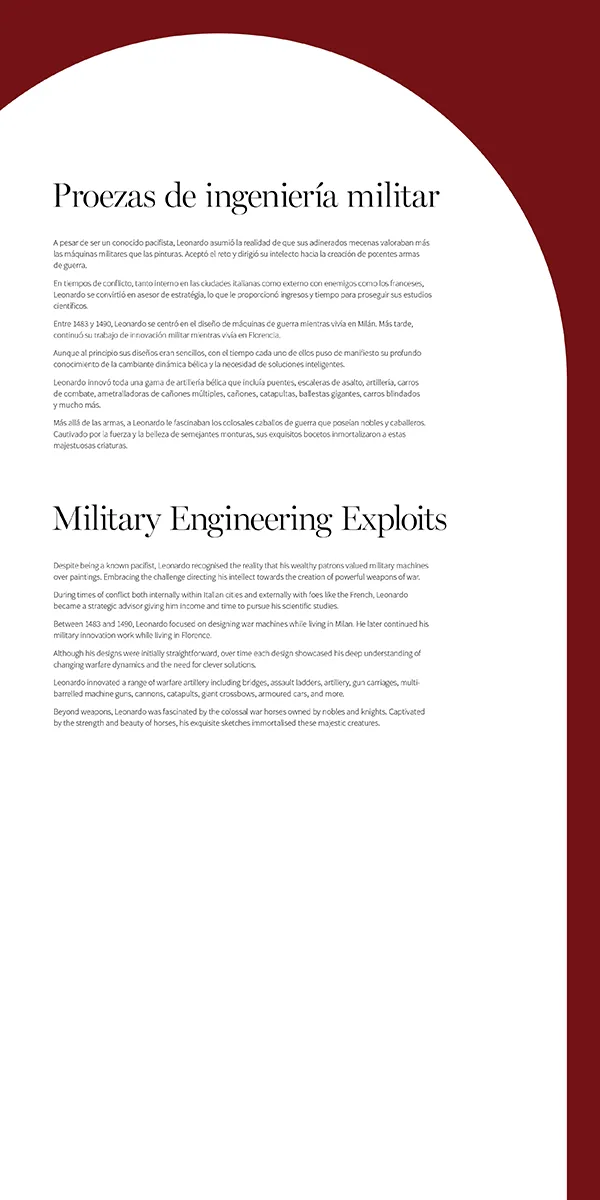

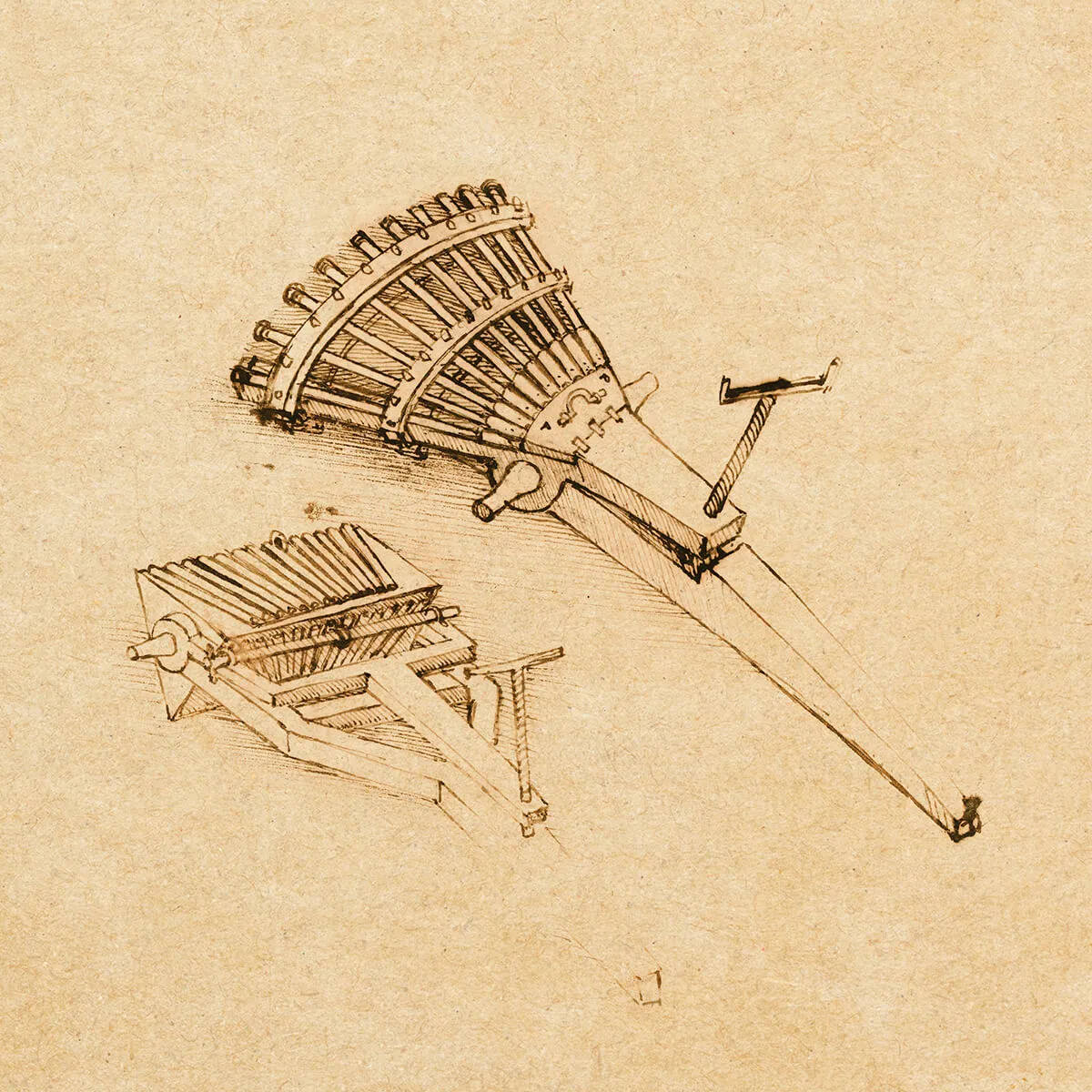

Three-Registered Gun Machine

At the top of this folio is a drawing of a multi-barreled

gun-machine. Leonardo wanted to increase the rate that

weapons could be fired, so he designed machines with

multiple cannons. These are perhaps the forerunner of the

modern machine gun.

This machine had 30 barrels, in three racks on a revolving

framework. As soon as the top row of 10 cannons had been

fired, the next rack was loaded; at the same time a third rack

was cooling off.

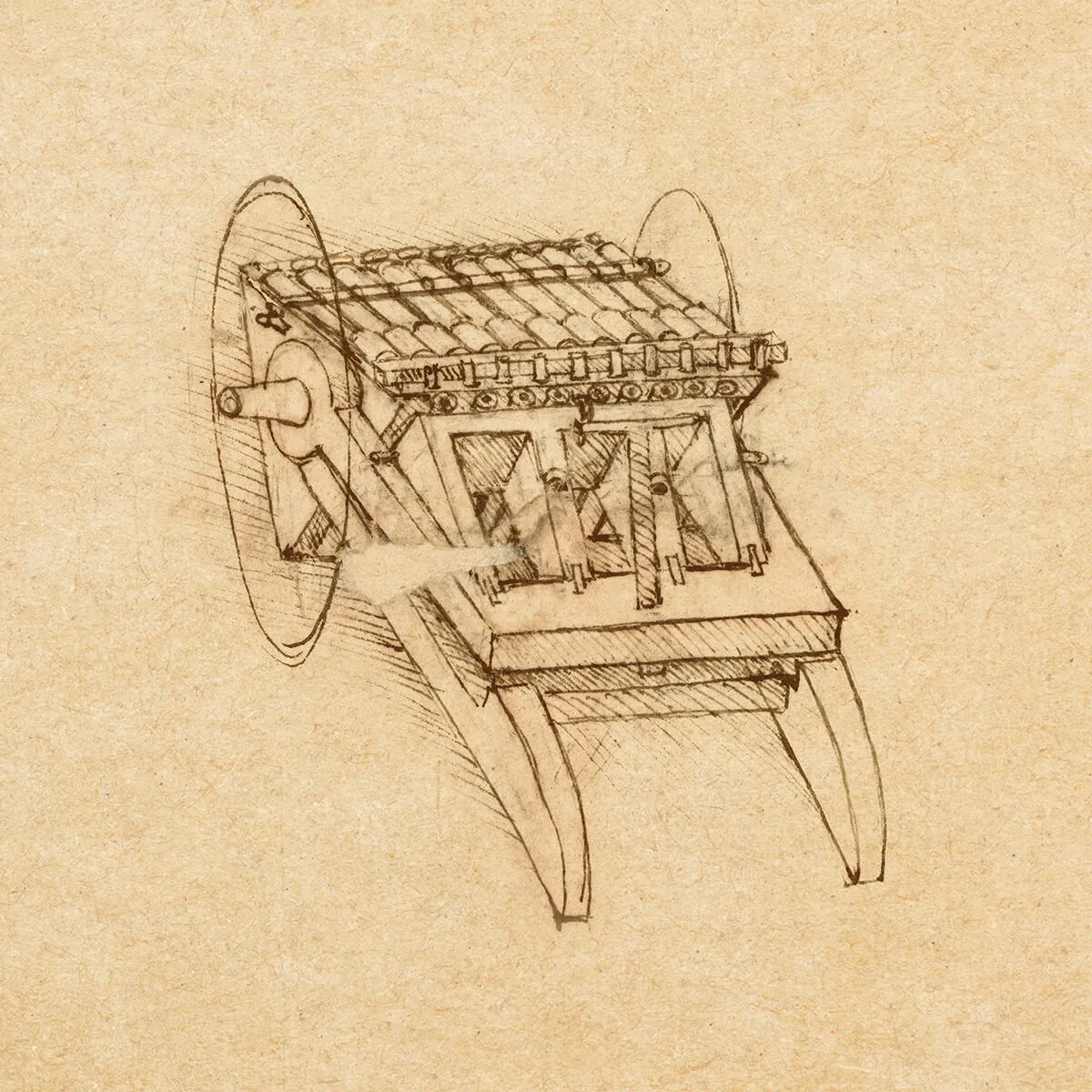

Cannon

This detailed sketch of a dreadful machine showcases Leonardo’s artistic and technical skills. He drew it for a potential patron, hoping to secure ongoing financial support. The drawing shows the parabolic trajectory of the shells when fired and how they exploded on impact.

The large cannons were mounted on sturdy wooden platforms. The firing angle could be adjusted using a wheel controlled by a worm screw, which was moved by a jack.

Steam Cannon

This machine was created to use steam power to launch cannonballs without using gunpowder.

The copper cannon, mounted on wheels, could be easily moved around the battlefield. To fire it, the cannon’s breech was heated, and water was added, creating steam pressure that shot the cannonball out of the barrel. This caused a loud blast and large clouds of steam. Leonardo got this idea from the Greek mathematician Archimedes.

Tank

Leonardo created a tank-like vehicle that could move in any direction and had cannons on all sides. A soldier in the turret would guide its movement.

To move the vehicle, eight men inside would turn cranks attached to trundle wheels, which connected to the four large wheels.

However, in Leonardo’s design, the wheels were set to turn in opposite directions. Also, it wasn’t clear who would load and fire the cannons. The idea of this armoured vehicle became a reality during World War I.

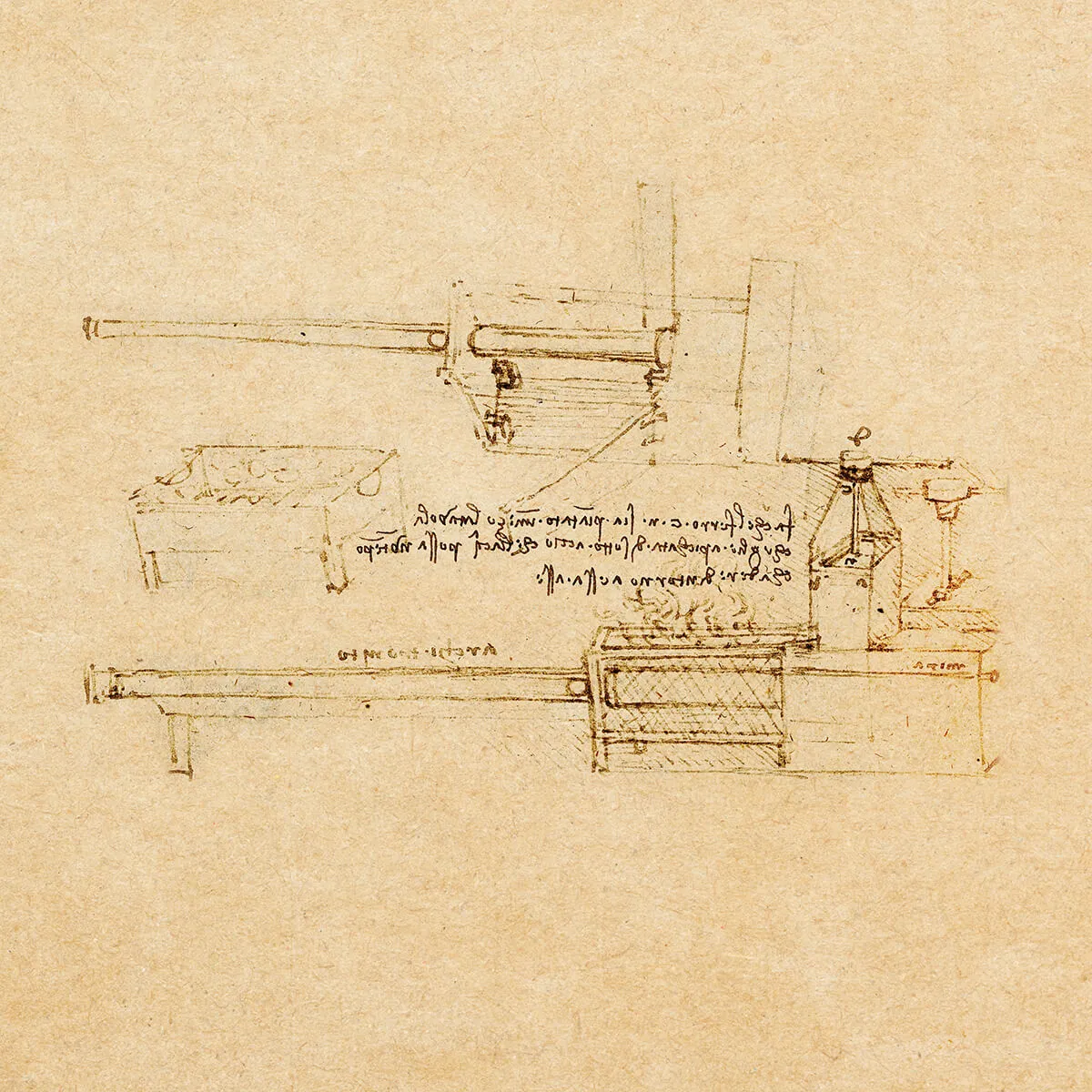

Multi-Directional Gun Machine

The middle drawing in the folio shows a machine with cannons set up in a fan shape. It could fire either one shot at a time or multiple shots at once.

This wheeled machine was designed to be easily moved to aim at the enemy. A crank at the back could adjust the height and direction of the shots. However, reloading this machine during battle would have been quite difficult.

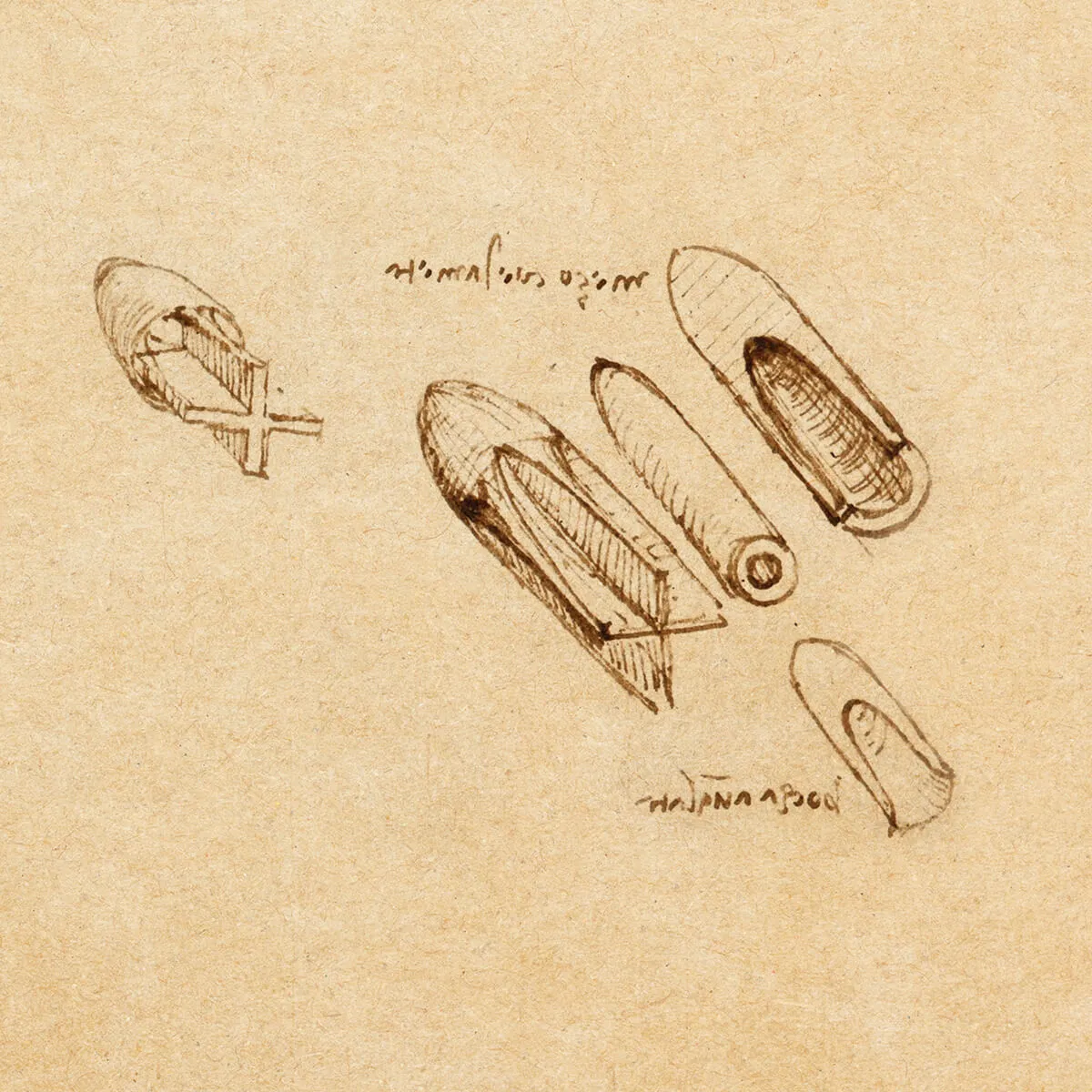

Ogival Bullet

Leonardo had studied how air and water currents influence the way that objects move. He recognised that air slows down the flight of a projectile and that the flight of a cannon ball was erratic.

He designed a new type of bullet, with a long pointed shape and directional wings to increase its aerodynamic efficiency and help it to fly straight and true.

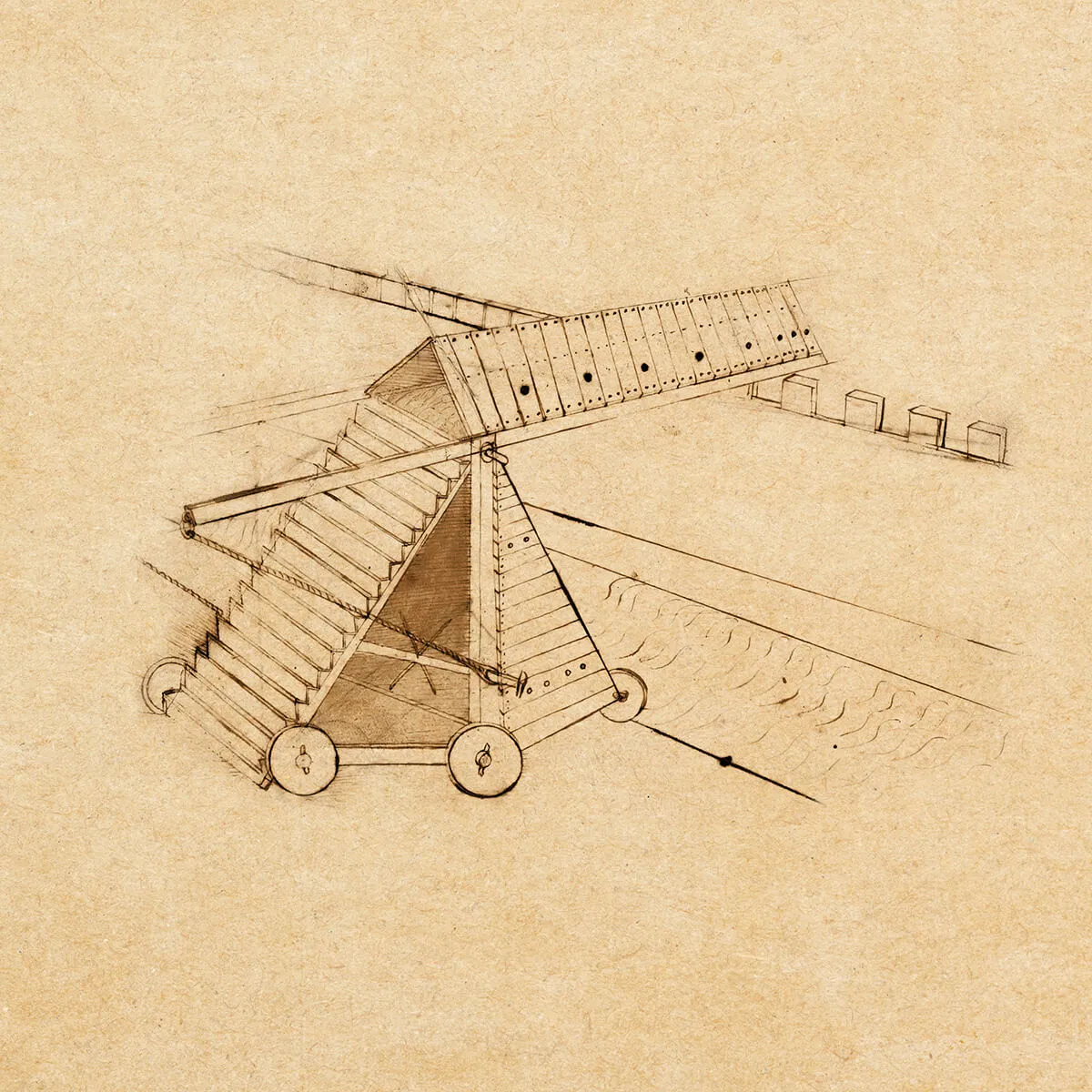

Covered Cart for Attacking Fortifications

Was this Leonardo’s version of the Trojan Horse? This massive wooden structure was designed to attack a castle or fortress.

The wheeled framework is pushed up to the walls, and then a long covered footbridge is lowered into place with ropes. The footbridge is long enough to cross a castle moat and reach the fortress walls.

Soldiers can then emerge from the framework, climb across the bridge, and break into the fortress.

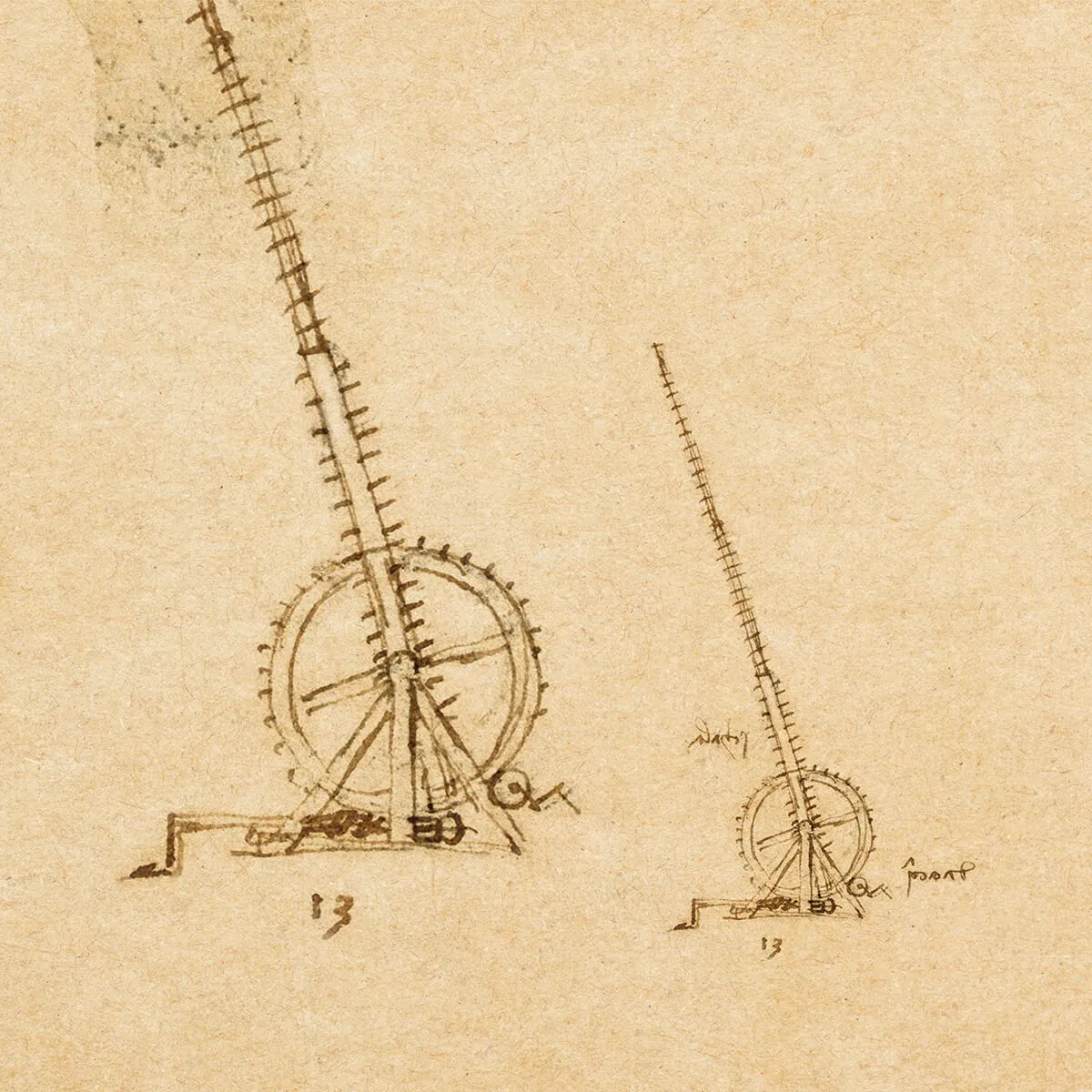

Assault Ladder

Leonardo drew many different types of assault ladders by which soldiers could scale the walls of an enemy fortress or castle.

This portable ladder can be lengthened or shortened, and inclined at different angles. The mechanism is a large toothed wheel which meshes with a worm screw.

A crank below the wheel sets the ladder in motion, raising or lowering it as needed. This scaling ladder is similar to those used by fire-fighters today.

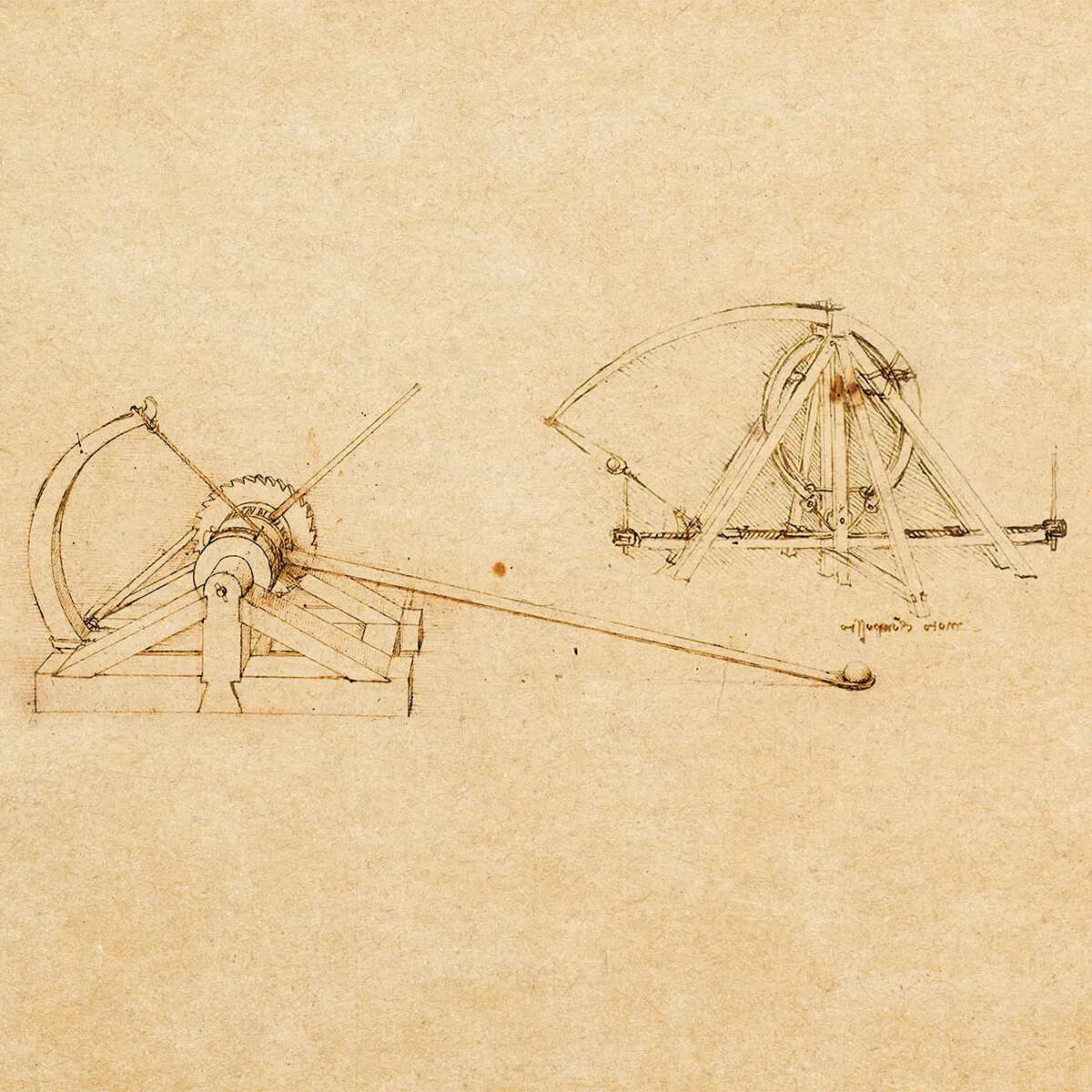

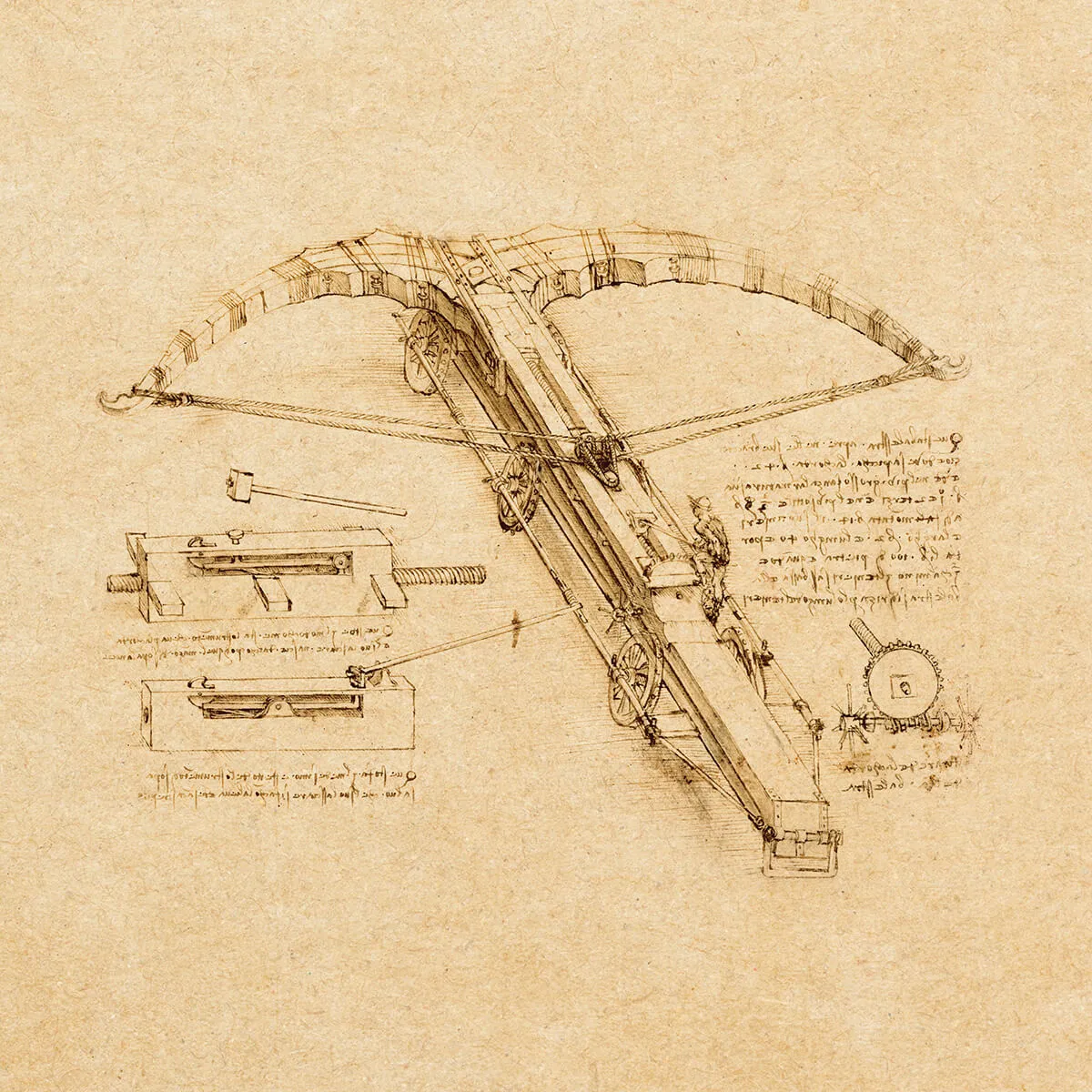

Catapult

Leonardo’s interest in military engineering started early. He filled many notebook pages with sketches of how to improve the catapult, one of the oldest war weapons.

In his designs, he explored the elasticity of different materials and how varying the tension might send the stone further, with more force, and greater accuracy against the enemy.

.svg)

Mona Lisa Revealed

Each year, more than nine million people go to the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa. But what they see today doesn’t quite match what Leonardo da Vinci painted centuries ago.

The painting has become tarnished and discoloured, making it look like it was painted in brown and green tones when originally Leonardo used fresh and delicate colours.

Over time, the materials he used have been affected by age and multiple restoration attempts. The wood support has shrunk, causing cracks, and chemical reactions between the paint and varnish have altered the portrait’s appearance.

French engineer Pascal Cotte had the rare opportunity to see the original Mona Lisa up close at the Louvre Museum in Paris. The painting was taken out from behind the bulletproof glass and frame so Cotte could photograph it in super high detail, with an extraordinary resolution of 240 megapixels.

After three hours of photography, Pascal Cotte produced thirteen high-resolution photos of the masterpiece using light wavelengths from ultraviolet to infrared to capture a variety of images.

Infrared light can be seen through the top layer of paint to show hidden drawings, pigments, and restoration work. By looking at each layer, we can understand more about how the Mona Lisa was made and changed over time, leading to the masterpiece we see today.

Taking photos of the Mona Lisa was just the beginning. It took over two years of analysis and discussions with experts to uncover 25 fascinating secrets about the painting.

And most importantly, you can admire Mona Lisa as Leonardo originally painted her.

Did You Know?

The actual size of the Mona Lisa is 77 x 53 cm (30.31 x 20.87 in).

‘Mona’ is the spelling used in English countries; ‘Monna’ is Italian, which is the spelling recommended by the Louvre.

Mona Lisa is referred to as La Joconde in France and La Gioconda in Italy.

The masterpiece is displayed in the Louvre Museum, Paris, as a Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo.

In Leonardo’s eyes, the Mona Lisa is incomplete. Starting the painting in 1503 and is thought to have ‘completed’ the work in 1514, but he never seemed quite satisfied. He kept the painting with him right up until he died in 1519, continually retouching and reworking.

Italian Origins to French Ownership

When King Francis I invited Leonardo to the Château du Clos Lucé in France in 1516, the Mona Lisa went with him. The king bought the painting for 4,000 écus in 1518, and so it was that the painting came to be in French hands – not Italian.

In the early 19th century, Mona Lisa came into the possession of Napoleon Bonaparte. He displayed the painting in his bedroom and also his bathroom, where water damage occurred to the varnish near the eye and chin.

Masterpiece Stolen, Now Safeguarded

In 1911, an Italian Louvre employee stole the Mona Lisa and hid it for two years. At the time, no one knew who stole the painting and the hunt spread far and wide. Even Pablo Picasso was implicated and questioned by police.

The thief, Vincenzo Peruggia, was caught when he tried to sell the painting to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence with the intent of returning it to its “rightful home”.

He was hailed for his patriotism in Italy, where he served only a few months jail time for his crime. It wasn’t until recently that a speck of orange paint was found on the Mona Lisa, thought to have been left there by Peruggia, who was also

a building painter.

Until the mid-19th century, the Mona Lisa was not well known. The painting gained wide appreciation when artists of the emerging symbolist movement discovered it, associating it with their ideas about the feminine mystique.

In 1956, the lower part of the painting was severely damaged when someone doused it with acid. On December 30 of that same year, Ugo Ungaza Villegas, a young Bolivian man, caused further damage by throwing a rock at it.

From December 1962 to March 1963, the French government lent Mona Lisa to the United States of America, to be displayed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Mona Lisa is now considered far too valuable to move and lives permanently behind a purpose-built bulletproof glass enclosure in the Louvre in Paris.

Artistic Rejuvenation

The enigmatic Mona Lisa has fascinated generations of art lovers.

Leonardo da Vinci’s skilful technique and use of glazes give the Mona Lisa beautiful, subtle colours. This technique is impossible to copy, so restoring this treasured artwork is very difficult.

The varnish layers added over time have mixed with the paint and glazes and trying to remove any layers could change the painting unintentionally.

With Pascal Cotte’s multispectral camera photography and detailed computer analysis, we can dig down through the layers of the Mona Lisa without changing the original brushstrokes.

We have been able to accurately reproduce the masterpiece, and reveal all the details of its history. And for the first time, see the Mona Lisa in full, vibrant colour – just as Leonardo intended.

Pigments and Binders

In the 15th century, artists had many different painting pigments made from natural materials, like stones and ores. Leonardo wrote about some of these in his Treatise on Painting.

While the specific ways to make pigments differed from place to place and artist to artist, they usually had similar basic ingredients. Pigments were often sold as powders and had to be mixed with a binder to make paint.

Before the 15th century, artists used eggs to bind paints in a method called ‘tempera.’ But for the Mona Lisa, Leonardo used a new binder made from oil, likely walnut oil, from the Netherlands. This new binder changed painting and led to what we now know as oil paints.

Lapis Lazuli – More Expensive than Gold

Lapis lazuli is a valuable blue gem used in painting since the Middle Ages. It’s crushed into a pigment called ultramarine, which was very expensive in Leonardo’s time. Painters at the time often charged extra for it or asked clients to provide it.

It seems Leonardo had some, as the whole sky in the Mona Lisa is made of lapis lazuli as it’s a beautiful deep blue colour.

Today, only one manufacturer in the world produces lapis lazuli powder as pure as that used by Leonardo da Vinci and it costs approximately $US20,000/kg. Most painters today use a synthetic version of aquamarine.

Virtual Varnish Removal

Using multispectral scanning on the Mona Lisa allowed researchers to see the varnish’s effect on each pixel. Once they digitally removed this effect, a clear image of how the Mona Lisa looked before varnish was revealed and the result is astonishing.

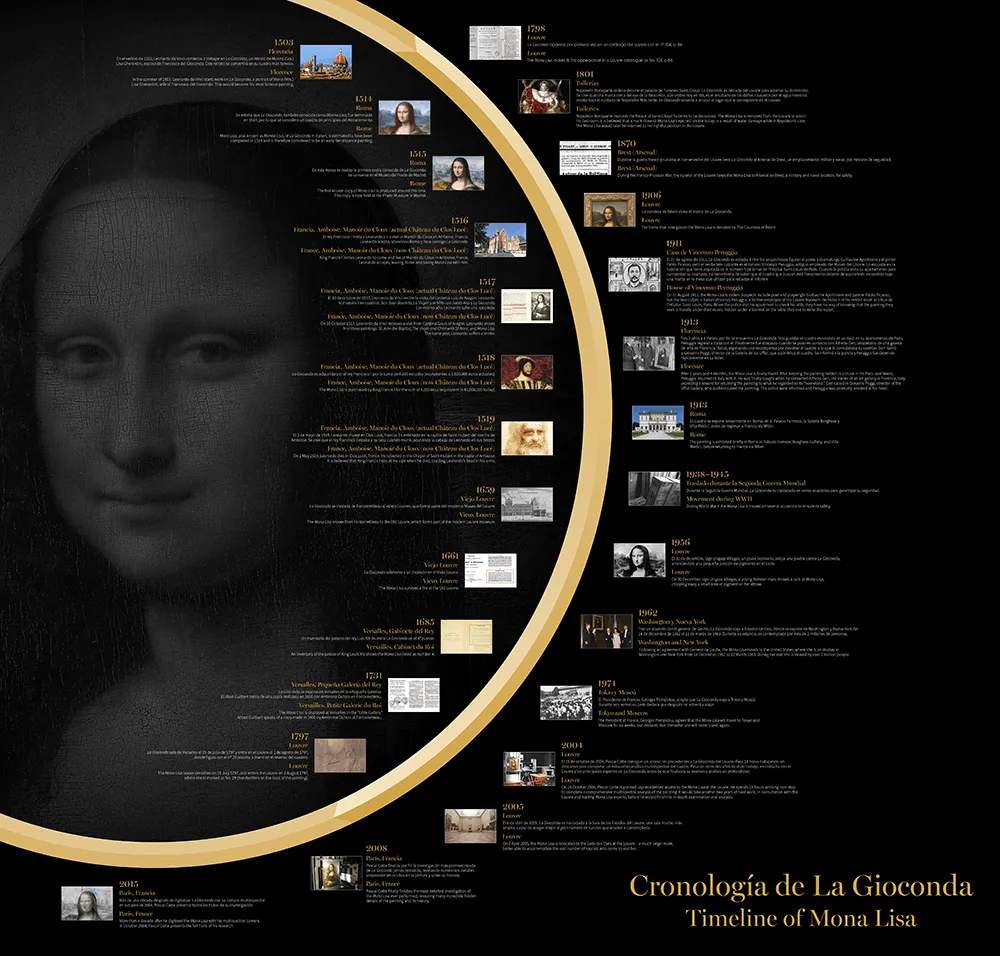

Timeline of Mona Lisa

1503, Florence

In the summer of 1503, Leonardo da Vinci starts work on La Gioconda, a portrait of Mona (Mrs.) Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo. This would become his most famous painting.

1514, Rome

Mona Lisa, also known as Monna Lisa, or La Gioconda in Italian, is estimated to have been completed in 1514 and is therefore considered to be an early Renaissance painting.

1515, Rome

The first known copy of Mona Lisa is produced around this time. This copy is now held at the Prado Museum in Madrid.

1516, France, Amboise

Manoir du Cloux

(now Château du Clos Lucé)

King Francis I invites Leonardo to come and live at Manoir du Cloux in Amboise, France. Leonardo accepts, leaving Rome and taking Mona Lisa with him.

1517, France, Amboise

Manoir du Cloux

(now Château du Clos Lucé)

On 10 October 1517, Leonardo da Vinci receives a visit from Cardinal Louis of Aragon. Leonardo shows him three paintings: St John the Baptist, The Virgin and Child with St Anne, and Mona Lisa. The same year, Leonardo suffers a stroke.

1518France, Amboise

Manoir de Cloux

(now Château du Clos Lucé)

The Mona Lisa is purchased by King Francis I for the sum of 4,000 écus (equivalent to €1,500,000 today).

1519,France, Amboise

Manoir du Cloux

(now Château du Clos Lucé)

On 2 May 1519, Leonardo dies in Clos Lucé, France. He is buried in the Chapel of Saint-Hubert in the castle of Amboise. It is believed that King Francis I was at his side when he died, cradling Leonardo’s head in his arms.

1659, Vieux Louvre

The Mona Lisa moves from Fontainebleau to the “Old Louvre,” which forms part of the modern Louvre museum.

1661, Vieux Louvre

The Mona Lisa survives a fire at the Old Louvre.

1685, Versailles

Cabinet du Roi

An inventory of the palace of King Louis XIV shows the Mona Lisa listed as number 4.

1731, Versailles

Petite Galerie du Roi

The Mona Lisa is displayed at Versailles in the “Little Gallery.” Abbot Guilbert speaks of a copy made in 1600 by Ambroise Dubois at Fontainebleau.

1797, Louvre

The Mona Lisa leaves Versailles on 15 July 1797, and enters the Louvre on 1 August 1797, where she is marked as No. 29 (handwritten on the back of the painting).

1798, Louvre

The Mona Lisa makes its first appearance in a Louvre catalogue as No. 104, p.84.

1801, Tuileries

Napoleon Bonaparte instructs the Palace of Saint-Cloud Tuileries to be decorated. The Mona Lisa is removed from the Louvre to adorn his bedroom. It is believed that a mark close to Mona Lisa’s eye, still visible today, is a result of water damage while in Napoleon’s care. The Mona Lisa would later be returned to her rightful position in the Louvre.

1870, Brest (Arsenal)

During the Franco-Prussian War, the curator of the Louvre takes the Mona Lisa to Arsenal de Brest, a military and naval location, for safety.

1906, Louvre

The frame that now graces the Mona Lisa is donated by The Countess of Béarn.

1911, House of Vincenzo Peruggia

On 21 August 1911, the Mona Lisa is stolen. Suspects include poet and playwright Guillaume Apollinaire and painter Pablo Picasso, but the true culprit is Italian Vincenzo Peruggia, a former employee of the Louvre Museum. He hides it in his rented room at 5 Rue de l’Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris. When the police visit his apartment to check his alibi, they have no way of knowing that the painting they seek is literally under their noses: hidden under a blanket on the table they use to write the report.

1913, Florence

After 2 years and 4 months, the Mona Lisa is finally found. After keeping the painting hidden in a trunk in his Paris apartment, Peruggia returned to Italy with it. He was finally caught when he contacted Alfredo Geri, the owner of an art gallery in Florence, Italy, expecting a reward for returning the painting to what he regarded as its "homeland." Geri called in Giovanni Poggi, director of the Uffizi Gallery, who authenticated the painting. The police were informed and Peruggia was promptly arrested at his hotel.

1913, Rome

The painting is exhibited briefly in Rome at Palazzo Farnese, Borghese Gallery, and Villa Medici, before returning to France via Milan.

1938–1945, Movement during WWII

During World War II the Mona Lisa is moved on several occasions to ensure its safety.

1956, Louvre

On 30 December, Ugo Ungaza Villegas, a young Bolivian man, throws a rock at Mona Lisa, chipping away a small area of pigment on her elbow.

1962, Washington and New York

Following an agreement with General de Gaulle, the Mona Lisa travels to the United States, where she is on display in Washington and New York from 14 December 1962 to 12 March 1963. During her visit she is viewed by over 2 million people.

1974, Tokyo and Moscow

The President of France, Georges Pompidou, agrees that the Mona Lisa will travel to Tokyo and Moscow for six weeks, but declares that thereafter she will never travel again.

2004, Louvre

On 19 October 2004, Pascal Cotte is granted unprecedented access to the Mona Lisa at the Louvre. He spends 18 hours working non-stop to complete a comprehensive multispectral analysis of the painting. It would take another two years of hard work, in consultation with the Louvre and leading Mona Lisa experts, before he would finish his in-depth examination and analysis.

2005, Louvre

On 6 April 2005, the Mona Lisa is relocated to the Salle des Etats at the Louvre – a much larger room, better able to accommodate the vast number of tourists who come to visit her.

2008, Paris, France

Pascal Cotte finally finishes the most detailed investigation of the Mona Lisa ever performed, revealing many incredible hidden details of the painting and its history.

2015, Paris, France

More than a decade after he digitised the Mona Lisa with his multispectral camera in October 2004, Pascal Cotte presents the full fruits of his research.

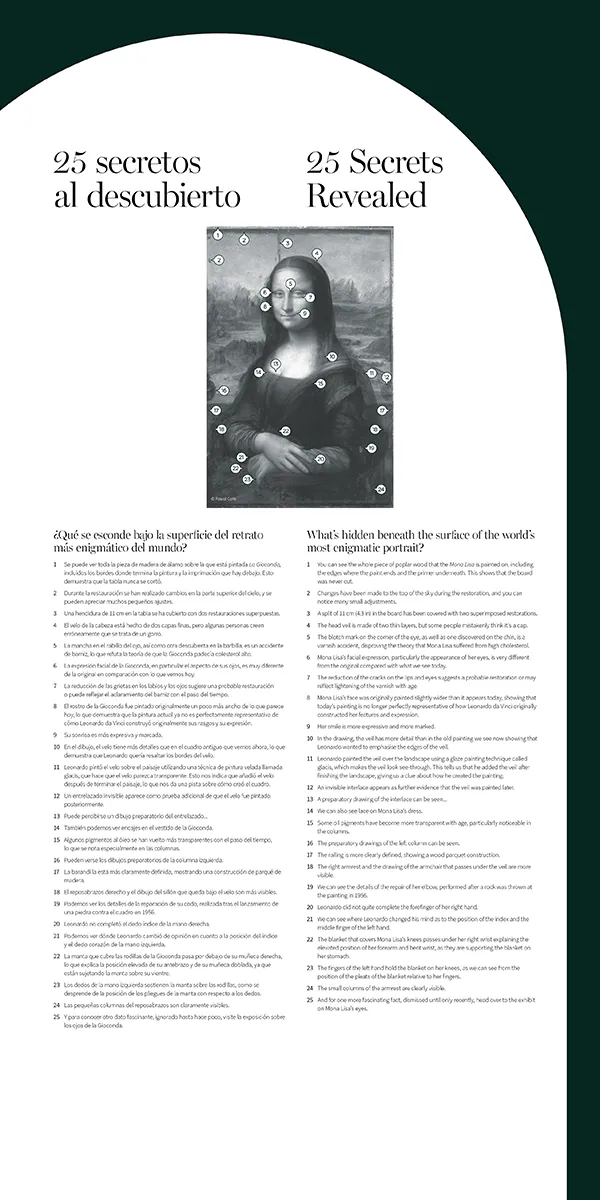

25 Secrets Revealed

What’s hidden beneath the surface of the world’s most enigmatic portrait?

1. You can see the whole piece of poplar wood that the Mona Lisa is painted on, including the edges where the paint ends and the primer underneath. This shows that the board was never cut.

2. Changes have been made to the top of the sky during the restoration, and you can notice many small adjustments.

3. A split of 11 cm (4.3 in) in the board has been covered with two superimposed restorations.

4. The head veil is made of two thin layers, but some people mistakenly think it's a cap.

5. The blotch mark on the corner of the eye, as well as one discovered on the chin, is a varnish accident, disproving the theory that Mona Lisa suffered from high cholesterol.

6. Mona Lisa’s facial expression, particularly the appearance of her eyes, is very different from the original compared with what we see today.

7. The reduction of the cracks on the lips and eyes suggests a probable restoration or may reflect lightening of the varnish with age.

8. Mona Lisa’s face was originally painted slightly wider than it appears today, showing that today’s painting is no longer perfectly representative of how Leonardo da Vinci originally constructed her features and expression.

9. Her smile is more expressive and more marked.

10. In the drawing, the veil has more detail than in the old painting we see now showing that Leonardo wanted to emphasise the edges of the veil.

11. Leonardo painted the veil over the landscape using a glaze painting technique called glacis, which makes the veil look see-through. This tells us that he added the veil after finishing the landscape, giving us a clue about how he created the painting.

12. An invisible interlace appears as further evidence that the veil was painted later.

13. A preparatory drawing of the interlace can be seen...

14. We can also see lace on Mona Lisa’s dress.

15. Some oil pigments have become more transparent with age, particularly noticeable in the columns.

16. The preparatory drawings of the left column can be seen.

17. The railing is more clearly defined, showing a wood parquet construction.

18. The right armrest and the drawing of the armchair that passes under the veil are more visible.

19. We can see the details of the repair of her elbow, performed after a rock was thrown at the painting in 1956.

20. Leonardo did not quite complete the forefinger of her right hand.21. We can see where Leonardo changed his mind as to the position of the index and the middle finger of the left hand.

22. The blanket that covers Mona Lisa’s knees passes under her right wrist explaining the elevated position of her forearm and bent wrist, as they are supporting the blanket on her stomach.

23. The fingers of the left hand hold the blanket on her knees, as we can see from the position of the pleats of the blanket relative to her fingers.

24. The small columns of the armrest are clearly visible.

25. And for one more fascinating fact, dismissed until only recently, head over to the exhibit on Mona Lisa’s eyes.

Mona Lisa Information Panels:

Colour Today

This image shows the Mona Lisa as she appears in the Louvre, in Paris, today. There is a sweetness to the soft light that falls upon her from the top left of the painting, and her delicate hands and the subtle veil on her head also contribute to this effect. One of her most striking features is her eyes, which seem to follow you as you move from left to right, yet do not gaze directly at you. The effect can be a little disconcerting and has sparked much discussion over the years.

The landscape behind the young lady comprises three horizontal sections. At the level of her chest, we see the ‘man-made’ section: a road on the right, and a river and bridge on the left. At the level of her neck the landscape becomes ‘harder’, with a deep lake and forest. Finally, towards the top of the painting we see the landscape become even harsher, with rocky mountains

disappearing into the fog.

It has been said that the sky could represent God. Indeed, many believe that the landscape is much more than a background, having deep philosophical undertones.

Image of Genuine Colour

Pascal Cotte’s multispectral camera has allowed us to accurately identify the pigments used in the Mona Lisa, allowing us to finally see her as Leonardo da Vinci intended. By recreating each of these pigments as they would have originally appeared, it was possible to generate a replica of the Mona Lisa that shows exactly how she looked when she had just been painted.

Pigment analysis has shown that the pigment used to paint the sky is composed of a deep blue gemstone called lapis lazuli mixed with white lead. The skin is painted with the powder of mercuric sulfide ore, known as vermilion, mixed with yellow lead and white lead. The paint used for the sleeves also contained white lead and yellow lead.

It is interesting to note that Leonardo has depicted the mountains in blue. This may seem strange at first, but in fact, mountains are depicted in blue in all of Leonardo’s paintings, including the Virgin of the Rocks. In his Treatise on Painting, Leonardo wrote, “You know that in an atmosphere of uniform density the most distant things seen through it, such as the mountains, in consequence of the great quantity of atmosphere, which is between your eye and them, will appear blue.”

Varnish Removed

Pascal Cotte’s multispectral camera gives us the unique ability to ‘virtually’ remove the influence of varnish. Physical removal of the varnish is impossible without damaging the previous artwork, as the varnish is now mixed with the underlying pigments to the point where one could not be removed without the other.

This simulation therefore offers a unique opportunity to look a little closer at art’s most mysterious character. Without the influence of the varnish on our perception of the painting, we are able to see details that were previously invisible.

See for yourself: the sleeves show more gold; the sky is a more vibrant blue; clouds are clearer; and the landscape takes on a different tone.

False Colour Infrared

Here we dig deeper still into the layers that underlie the Mona Lisa we know. The optical properties of infrared light allow it to penetrate beyond the visible surface layer of a painting to reveal underlying details that would otherwise have remained invisible. Infrared light is not visible to the human eye, but we can simulate it with visible light wavelengths using scientific data obtained from the multispectral camera.

Here we see a virtual image representing the results of Cotte’s infrared scan.

As you look at this image, you are effectively viewing it as if your eyes had the superhuman ability to detect infrared light. The first thing you’ll notice is that the colour spectrum of the painting has completely changed towards reds and oranges. But this ‘false colour’ is only one effect of the infrared light. It also allows you to see beyond the visible surface layer. Hidden beneath the surface are details of retouching and restorations, and underlying drawings and pigments. These details represent the ‘secrets’ that Pascal Cotte was able to identify and analyse to give us a much deeper understanding of a complex and mysterious artwork.

Reverse False Colour

InfraredWhen Pascal Cotte converted the infrared image of the Mona Lisa into images with visible colours, he was able to create multiple images using different parts of the visible light spectrum.

In this image, Cotte has converted the infrared information into shades of blue, rather than reds and oranges as in the previous image. This provides greater detail in the deep, dark areas of the painting.

No specific discoveries came from the image, but it formed one more aspect of a thorough, detailed investigation, helping to consolidate and build upon the 25 ‘secrets’ Pascal Cotte was ultimately able to compile.

Mona Lisa Replica

Here you see the Mona Lisa as she appears today, in true colour and size, exactly as Pascal Cotte saw her when he photographed the real Mona Lisa at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France.

Few paintings are as treasured and as protected as the Mona Lisa. Kept in a climate-controlled room behind bulletproof glass, only a privileged minority will ever have the opportunity to see her up close. This replica gives us a rare opportunity to discover what the back of the painting reveals about Mona Lisa’s rich and tumultuous history.

Where the board has split, two butterfly clips were originally used to repair it. Now only the bottom clip remains, and how and when the top butterfly clip, beige in colour, was lost remains a mystery.

Among the writings and repairs, notice the address ‘Au garde des Tableaux à Versailles… bureau du Directeur’ (‘to the Painting guardian at Versailles… office of the Director’). This likely dates from when King Louis XIV, who owned the painting at the time, moved it from the Palace of Fontainebleau to his new residence at the Palace of Versailles.

At the top left you can read the word Joconde, the French name for Mona Lisa. On the bottom right you will see the red stamp of the Musée Royal (‘Royal Museum’). The fleur-de‑lys is the symbol of the French King, while the number 316 refers to the position of Mona Lisa in the museum’s collection.

In the middle of the panel, you can make out the number 29. This is the number of Mona Lisa in the list of paintings that were moved from Versailles to the Louvre. However, the date and meaning of the letter ‘H’ above it are unknown.

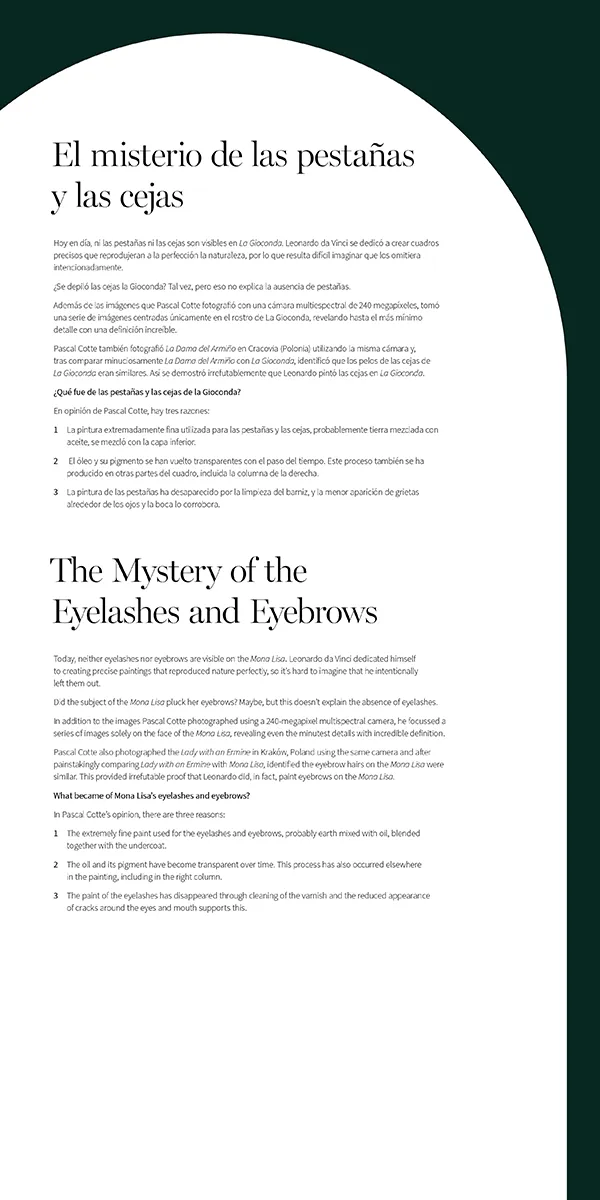

The Mystery of the Eyelashes and Eyebrows

Today, neither eyelashes nor eyebrows are visible on the Mona Lisa. Leonardo da Vinci dedicated himself to creating precise paintings that reproduced nature perfectly, so it’s hard to imagine that he intentionally left them out.

Did the subject of the Mona Lisa pluck her eyebrows? Maybe, but this doesn’t explain the absence of eyelashes.

In addition to the images Pascal Cotte photographed using a 240-megapixel multispectral camera, he focussed a series of images solely on the face of the Mona Lisa, revealing even the minutest details with incredible definition.

Pascal Cotte also photographed the Lady with an Ermine in Kraków, Poland using the same camera and after painstakingly comparing Lady with an Ermine with Mona Lisa, identified the eyebrow hairs on the Mona Lisa were similar. This provided irrefutable proof that Leonardo did, in fact, paint eyebrows on the Mona Lisa.

What became of Mona Lisa’s eyelashes and eyebrows?

In Pascal Cotte’s opinion, there are three reasons:

1. The extremely fine paint used for the eyelashes and eyebrows, probably earth mixed with oil, blended together with the undercoat.

2. The oil and its pigment have become transparent over time. This process has also occurred elsewhere in the painting, including in the right column.

3. The paint of the eyelashes has disappeared through cleaning of the varnish and the reduced appearance of cracks around the eyes and mouth supports this.

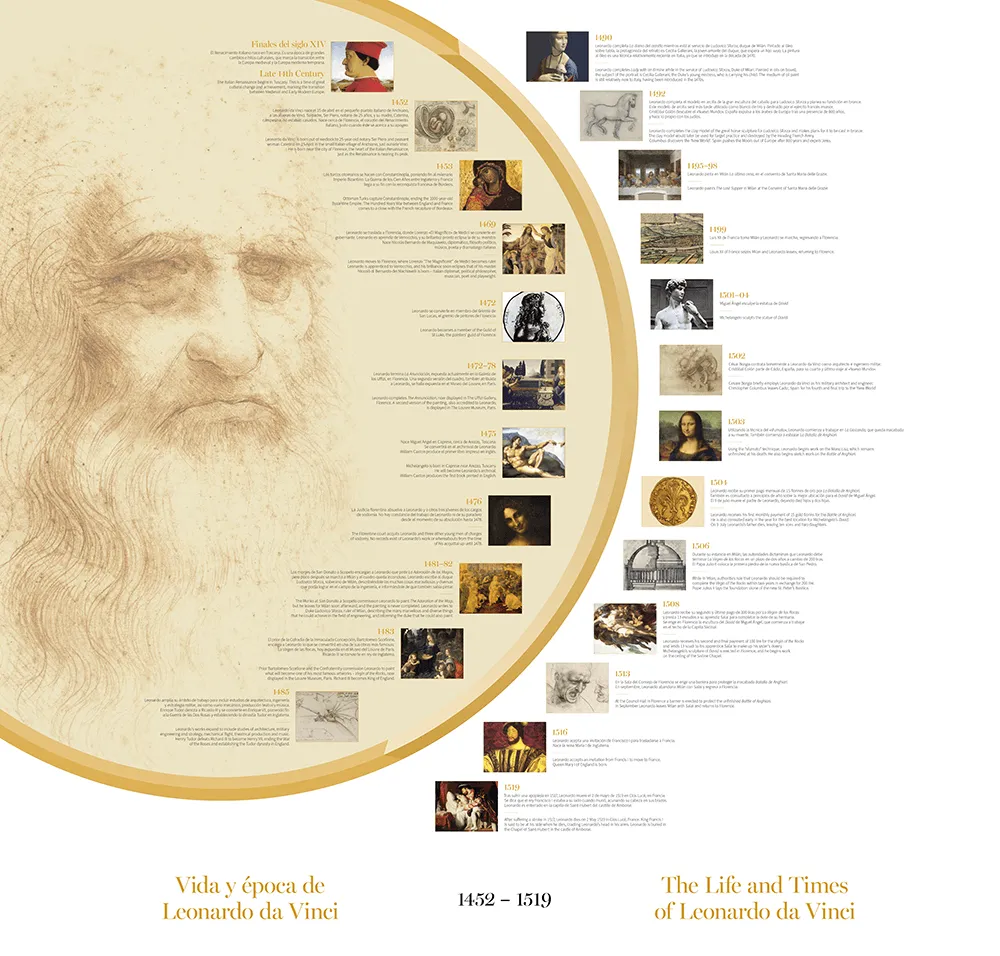

The Life and Times of Leonardo da Vinci – 1452–1519

Late 14th century

The Italian Renaissance begins in Tuscany. This is a time of great cultural change and achievement, marking the transition between Medieval and Early Modern Europe.

1452

Leonardo da Vinci is born out of wedlock to 25-year-old notary Ser Piero and peasant woman Caterina on 15 April in the small Italian village of Anchiano, just outside Vinci. He is born near the city of Florence, the heart of the Italian Renaissance, just as the Renaissance is nearing its peak.

1453

Ottoman Turks capture Constantinople, ending the 1,000-year-old Byzantine Empire. The Hundred Years War between England and France comes to a close with the French recapture of Bordeaux.

1469

Leonardo moves to Florence, where Lorenzo “The Magnificent” de Medici becomes ruler. Leonardo is apprenticed to Verrocchio, and his brilliance soon eclipses that of his master.

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli is born – Italian diplomat, political philosopher, musician, poet and playwright.

1472

Leonardo becomes a member of the Guild of St Luke, the painters’ guild of Florence.

1472–78

Leonardo completes Annunciation, now displayed in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. A second version of the painting, also accredited to Leonardo, is displayed in the Louvre Museum, Paris.

1475

Michelangelo is born in Caprese, near Arezzo, Tuscany. He will become Leonardo’s archrival.

William Caxton produces the first book printed in English.

1476

The Florentine court acquits Leonardo and three other young men of charges of sodomy. No records exist of Leonardo’s work or whereabouts from the time of his acquittal up until 1478.

1481–82

The Monks at San Donato a Scopeto commission Leonardo to paint The Adoration of the Magi, but he leaves for Milan soon afterward, and the painting is never completed. Leonardo writes to Duke Ludovico Sforza, ruler of Milan, describing the many marvellous and diverse things that he could achieve in the field of engineering, and informing the duke that he could also paint.

1483

Prior Bartolomeo Scorlione and the Confraternity commission Leonardo to paint what will become one of his most famous artworks – the Virgin of the Rocks, now displayed in the Louvre Museum, Paris.

Richard III becomes King of England.

1485

Leonardo’s works expand to include studies of architecture, military engineering and strategy, mechanical flight, theatrical production and music.

Henry Tudor defeats Richard III to become Henry VII, ending the War of the Roses and establishing the Tudor dynasty in England.

1490

Leonardo completes Lady with an Ermine while in the service of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. Painted in oils on board, the subject of the portrait is Cecilia Gallerani, the Duke’s young mistress, who is carrying his child. The medium of oil paint is still relatively new to Italy, having been introduced in the 1470s.

1492

Leonardo completes the clay model of the great horse sculpture for Ludovico Sforza and makes plans for it to be cast in bronze. The clay model would later be used for target practice and destroyed by the invading French Army.

Columbus discovers the “New World.”

Spain pushes the Moors out of Europe after 800 years and expels Jews.

1495–98

Leonardo paints The Last Supper in Milan at the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie.

1499

Louis XII of France seizes Milan and Leonardo leaves, returning to Florence.

1501–04

Michelangelo sculpts the statue of David.

1502

Cesare Borgia briefly employs Leonardo da Vinci as his military architect and engineer.

Christopher Columbus leaves Cadiz, Spain, for his fourth and final trip to the “New World.”

1503

Using the “sfumato” technique, Leonardo begins work on the Mona Lisa, which remains unfinished at his death. He also begins sketch work on the Battle of Anghiari.

1504

Leonardo receives his first monthly payment of 15 gold florins for the Battle of Anghiari. He is also consulted early in the year for the best location for Michelangelo’s David. On 9 July Leonardo’s father dies, leaving ten sons and two daughters.

1506

While in Milan, authorities in Milan rule that Leonardo must complete the Virgin of the Rocks within two years in exchange for 200 lire.

Pope Julius II lays the foundation stone of the new St. Peter’s Basilica.

1508

Leonardo receives his second and final payment of 100 lire for the Virgin of the Rocks and lends 13 scudi to his apprentice Salai to make up his sister’s dowry.

Michelangelo’s sculpture of David is erected in Florence, and he begins work on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

1513

At the Council Hall in Florence a barrier is erected to protect the unfinished Battle of Anghiari. In September Leonardo leaves Milan with Salai and returns to Florence.

1516

Leonardo accepts an invitation from Francis I to move to France.